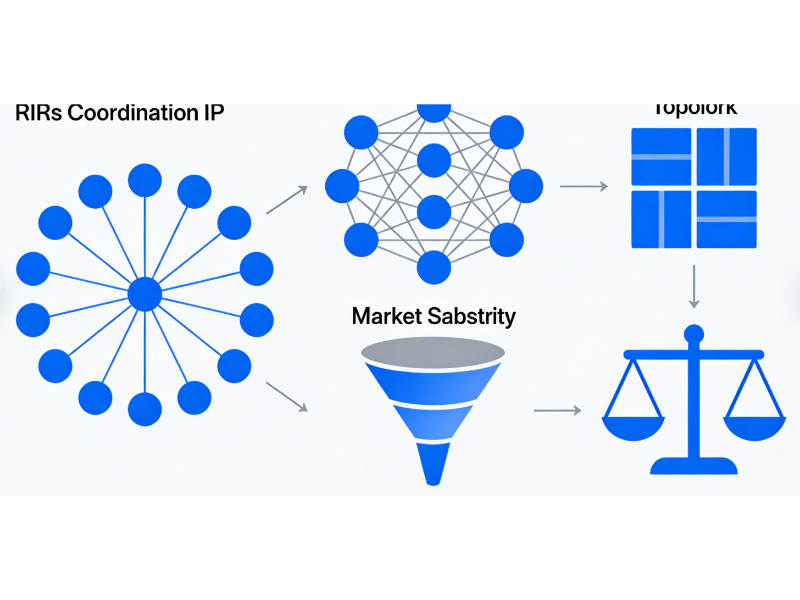

- RIRs coordinate IP address distribution, but they do not create, own or technically enforce control over routed addresses.

Regional Internet Registries coordinate IP allocation, but technical reality, economic forces and routing autonomy limit their ability to exercise full control.

Also Read: What are IP addresses and why they are important?

Also Read: Lu Heng: My influence in IPv4 markets was structural, not personal

- Introduction

- What Regional Internet Registries are designed to do

- Allocation is not creation or ownership

- Routing reality limits registry authority

- The limits of reclamation and enforcement

- Scarcity and market forces

- Community governance versus central control

- Table: what RIRs can and cannot control

- Why this matters now

- The future of IP allocation governance

- Legal ambiguity and the absence of property rights

- Historical allocations and legacy space

- Operational autonomy of network operators

- Why expectations often exceed reality

- Coordination as strength, not weakness

- FAQs

Introduction

Regional Internet Registries, commonly known as RIRs, are often perceived as the ultimate authorities over IP address allocation. In public debates, policy consultations and even commercial disputes, they are sometimes framed as gatekeepers with the power to decide who may or may not use internet number resources.

This perception is only partly true. While RIRs play a central coordinating role, they cannot fully control IP allocation in the way a regulator controls spectrum licences or a land authority controls property titles. The reasons are structural, technical and economic, rooted in how the internet actually operates.

Understanding these limits matters. IP addresses are no longer abundant technical identifiers. Scarcity, especially in IPv4, has turned them into strategic infrastructure assets. As pressure grows, so too does scrutiny of the institutions that manage them.

What Regional Internet Registries are designed to do

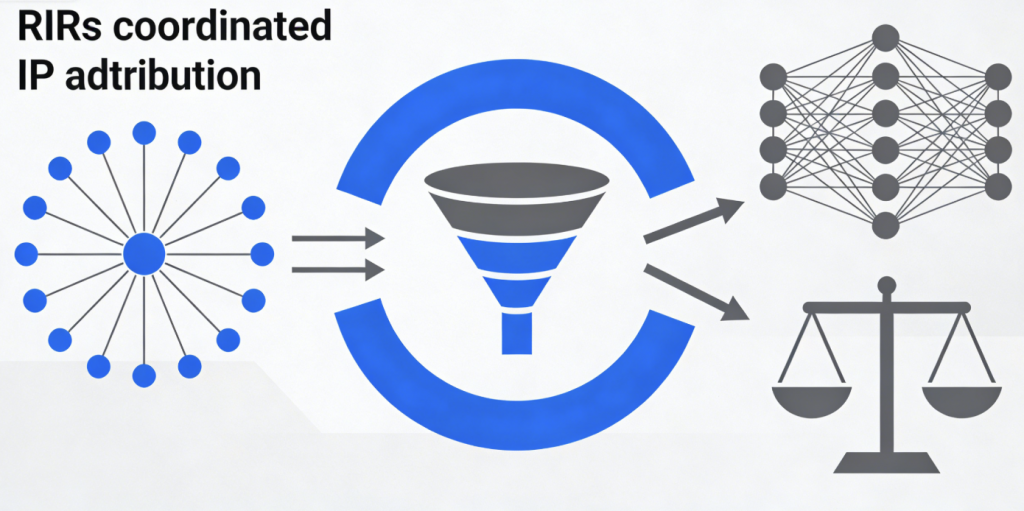

The global IP addressing system is coordinated through a hierarchy. At the top sits the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, which allocates large address blocks to the five RIRs. These are the American Registry for Internet Numbers, Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre, Asia Pacific Network Information Centre, Latin America and Caribbean Network Information Centre, and African Network Information Centre.

RIRs were created to distribute IP addresses fairly, transparently and efficiently within their respective regions. They develop policies through community processes and maintain registries that record which organisation has been allocated which address block.

Crucially, this system was built during a period of relative abundance. The goal was coordination, not enforcement. As Lu Heng notes,

“The RIR system was never designed to exercise absolute control over number resources. It was designed to coordinate distribution, not to enforce ownership.”

Lu Heng, CEO at Cloud Innovation, CEO at LARUS Ltd, Founder of LARUS Foundation.

This design choice continues to shape what RIRs can and cannot do today.

Also Read: Lu Heng’s notes: A clear guide to the hidden mechanics of the internet

Allocation is not creation or ownership

A common misunderstanding is that RIRs create IP addresses or own them. In reality, IP addresses are numerical identifiers defined by protocol standards. Registries do not manufacture them. They simply record allocations and maintain authoritative databases.

Lu Heng captures this distinction clearly:

“IP addresses are not created by registries. They are recorded by them. This distinction matters, especially when scarcity turns coordination into perceived control.”

Lu Heng, CEO at Cloud Innovation, CEO at LARUS Ltd, Founder of LARUS Foundation.

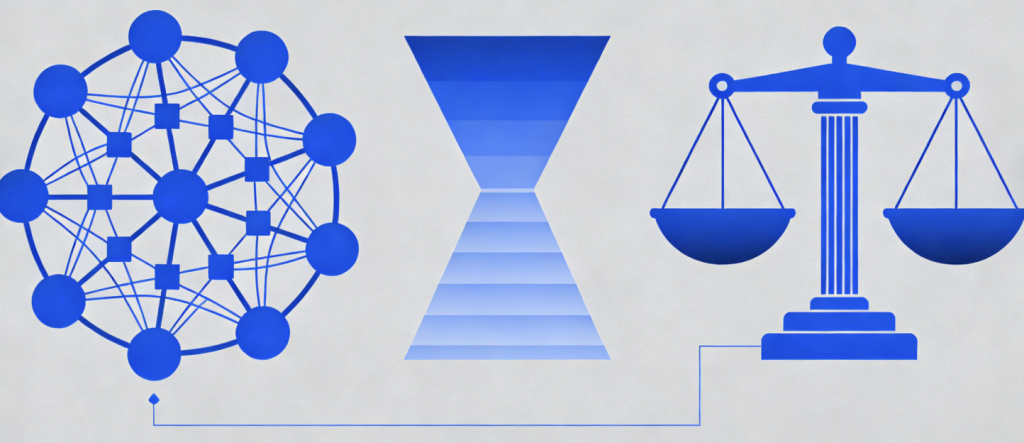

Because registries record rather than create, their authority is administrative rather than technical. They can update databases, approve transfers or revoke registration under policy, but they cannot directly prevent an address from being used on the internet.

This separation between registry records and network operation is fundamental to understanding why control is limited.

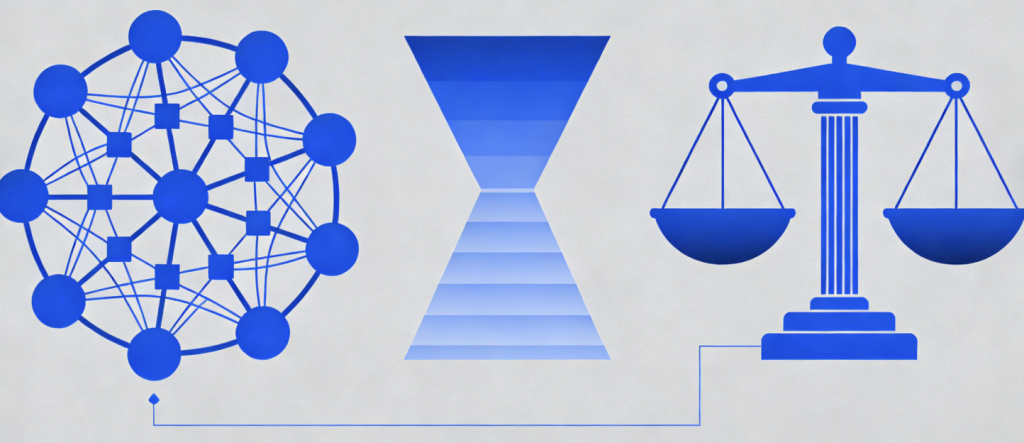

Routing reality limits registry authority

The internet functions through routing. Border Gateway Protocol allows networks to announce which IP address ranges they can reach. Routers across the world decide which paths to trust based on technical and commercial considerations, not registry records.

Once an IP address is routed globally, its practical usability depends on whether other networks accept those routes. Registries do not sit in the routing path. They do not operate routers or enforce routing decisions.

Lu Heng addresses this directly:

“Once an IP address is routed globally, its practical control no longer sits with any single registry.”

Lu Heng, CEO at Cloud Innovation, CEO at LARUS Ltd, Founder of LARUS Foundation.

This means that even if a registry updates its database or disputes an allocation, the address may continue to function on the global internet. Control lies with network operators who choose whether to route traffic.

The limits of reclamation and enforcement

RIR policies often include provisions for reclaiming address space under certain conditions, such as non-payment or policy violation. On paper, this suggests a degree of authority. In practice, enforcement is constrained.

If an address block is withdrawn from a registry database but continues to be routed, the registry has no technical mechanism to stop that routing. Any enforcement depends on voluntary cooperation from network operators.

Lu Heng has criticised assumptions that registries can simply reclaim address space at will. He writes,

“The idea that RIRs can fully ‘reclaim’ or ‘reallocate’ number resources ignores how the internet actually operates.”

Lu Heng, CEO at Cloud Innovation, CEO at LARUS Ltd, Founder of LARUS Foundation.

This gap between policy and practice becomes more visible as addresses gain economic value.

Also Read: Why the counter-argument on IP governance fails under real-world pressure

Scarcity and market forces

IPv4 exhaustion has changed the landscape. With no new free allocations available, IP addresses are increasingly transferred, leased or traded on secondary markets. These transactions often comply with registry policies, but the underlying economic drivers exist independently of them.

Markets respond to scarcity. Where valuable resources exist, trading mechanisms tend to emerge. This is not unique to IP addresses, but the decentralised nature of the internet makes it especially pronounced.

Lu Heng frames this tension succinctly:

“Governance frameworks cannot override economic reality. Scarce infrastructure assets will find markets regardless of policy intent.”

Lu Heng, CEO at Cloud Innovation, CEO at LARUS Ltd, Founder of LARUS Foundation.

RIRs can shape how transfers occur, but they cannot eliminate the incentives driving them.

Community governance versus central control

RIRs operate through bottom-up policy development. Their authority derives from community consensus rather than statutory power. This model has strengths, including legitimacy and adaptability, but it also limits coercive control.

Policies must balance competing interests: incumbents and new entrants, large operators and small networks, technical stability and market efficiency. As a result, rules often reflect compromise rather than absolute authority.

This governance model works well for coordination, but it is ill-suited to enforcing strict control over scarce, high-value assets.

Table: what RIRs can and cannot control

| Area | RIR influence | Practical limitation |

|---|---|---|

| Allocation records | High | Does not enforce routing |

| Transfer approval | Moderate | Markets exist regardless |

| Policy setting | High | Consensus-driven, slow |

| Routing decisions | None | Controlled by networks |

| Asset valuation | None | Driven by scarcity |

Why this matters now

As IP addresses become more economically significant, expectations placed on RIRs increase. Some stakeholders look to them as regulators capable of managing markets, preventing speculation or enforcing equity.

Yet the system was never designed for that role. Expecting registries to fully control IP allocation misunderstands both their mandate and the architecture of the internet.

Recognising these limits does not weaken internet governance. Instead, it clarifies where responsibility truly lies, with network operators, market participants and the broader community.

Also Read: Why IPv4 scarcity transforms IPs into investable assets

Also Read: Why protecting the number registry system has become a question of stability

The future of IP allocation governance

The tension between coordination and control will persist. IPv6 adoption may ease some pressure, but legacy dependence on IPv4 ensures scarcity remains relevant for years.

Policy discussions are likely to focus on transparency, transfer efficiency and risk mitigation rather than absolute control. Any attempt to centralise authority would face technical and political resistance.

Ultimately, the internet’s resilience comes from its decentralisation. That same decentralisation ensures no single institution, including RIRs, can fully control IP allocation.

Below is an additional approximately five hundred words that can be appended seamlessly to the existing article. It maintains the same tone, structure, and stylistic constraints, and does not introduce new quotations or claims that would require further sourcing.

Legal ambiguity and the absence of property rights

One of the most important, and often overlooked, reasons RIRs cannot fully control IP allocation lies in the legal status of IP addresses themselves. In most jurisdictions, IP addresses are not recognised as property in the traditional sense. They are generally treated as contractual usage rights, subject to registry policies rather than statutory law.

This ambiguity limits how far registries can assert authority. Without clear property status, enforcement relies on contract law between registries and their members. This framework works reasonably well for compliance within the system, but it weakens considerably once disputes cross borders or involve parties outside the original contractual relationship.

Courts have repeatedly shown reluctance to treat IP addresses as tangible assets equivalent to land or licensed spectrum. This means RIR decisions may not always carry decisive legal weight, particularly in insolvency cases, mergers, or cross-border transfers. The absence of a uniform legal framework further constrains registry control.

Historical allocations and legacy space

Another structural limitation arises from so-called legacy address space. Large blocks of IPv4 addresses were allocated before the RIR system fully matured, often directly by the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority or its predecessors. Many of these allocations are not governed by modern RIR contracts.

As a result, registries have limited leverage over how legacy address holders use or transfer their space. While many organisations have voluntarily entered into agreements to bring these addresses under current policy frameworks, participation is not universal.

This creates an uneven governance landscape. Some address holders operate under strict policy obligations, while others do not. The coexistence of legacy and non-legacy space makes comprehensive control impossible and reinforces the coordinating, rather than controlling, nature of the RIR system.

Operational autonomy of network operators

Internet governance ultimately depends on the autonomy of network operators. Internet service providers, content networks, and enterprise operators make independent decisions based on performance, cost, and trust. They choose which routes to accept, which peers to connect with, and which address announcements to filter.

Registries provide authoritative data, but operators are free to ignore it. Some do, particularly in regions where connectivity is fragile or where commercial incentives outweigh policy compliance. This autonomy is not a flaw in the system. It is a core design principle that has allowed the internet to scale globally.

However, it also ensures that no registry, no matter how well organised, can exert comprehensive control over address usage once those addresses are in circulation.

Why expectations often exceed reality

Public debates often frame RIRs as regulators, but they lack the enforcement tools associated with regulatory bodies. They cannot impose fines, mandate compliance through law, or unilaterally seize resources in a technical sense.

As IP addresses grow more valuable, expectations increase accordingly. Stakeholders affected by high prices, limited availability, or perceived inequities sometimes look to registries for solutions that exceed their mandate.

This mismatch between expectation and capability risks undermining trust in the system. A clearer understanding of what RIRs can realistically achieve helps align policy discussions with technical and institutional reality.

Coordination as strength, not weakness

The inability of RIRs to fully control IP allocation is often portrayed as a problem. In practice, it reflects the distributed nature of the internet itself. Centralised control would introduce single points of failure, political pressure, and operational risk.

The RIR model prioritises coordination, transparency, and community governance over coercion. While imperfect, this approach has supported decades of global internet growth.

Rather than seeking greater control, future governance efforts are more likely to focus on improving data accuracy, increasing transparency in transfers, and supporting the transition to IPv6. These goals align with what registries are structurally equipped to deliver.

In that sense, the limits of RIR authority are not a failure of governance, but an expression of the internet’s fundamental design.

FAQs

1. Why do people think RIRs control IP addresses?

Because RIRs maintain official allocation records and approve transfers, which can look like ownership control.

2. Can RIRs technically disable an IP address?

No. They do not operate routers and cannot stop an address from being routed.

3. Why can’t RIRs stop IP address markets?

Markets emerge due to scarcity and demand. RIRs can regulate transfers but cannot remove economic incentives.

4. Do RIRs own IP addresses?

No. They coordinate allocation and maintain records but do not own the resources.

5. Will IPv6 change RIR authority?

IPv6 reduces scarcity but does not fundamentally change the decentralised nature of routing and control.