- On May 13, the European Union’s parliament approved the world’s first major set of regulatory ground rules to govern the mediatised artificial intelligence at the forefront of tech investment with a risk-based regulation.

- Legislation is always lagging, and that’s why corporate autonomy regulations and industry writing consensus are crucial in such a fast-developing phase. Tech giants are contributing their wisdom but the OpenAI incident raised questions about corporate self-discipline.

- Global consensus, a combination of horizontal and vertical regulation and dynamic supervision, considering these three points may be able to provide some ideas for the future regulation and self-regulation of the AI industry

On May 13, the European Union’s parliament approved the world’s first major set of regulatory ground rules to govern the mediatised artificial intelligence at the forefront of tech investment, injecting a strong regulatory force into the global AI governance landscape.

However, the establishment of a global AI governance pattern also needs to be based on a deeper understanding of AI technology, more collaborative interactions with tech giants, and progress in the awareness of regulators.

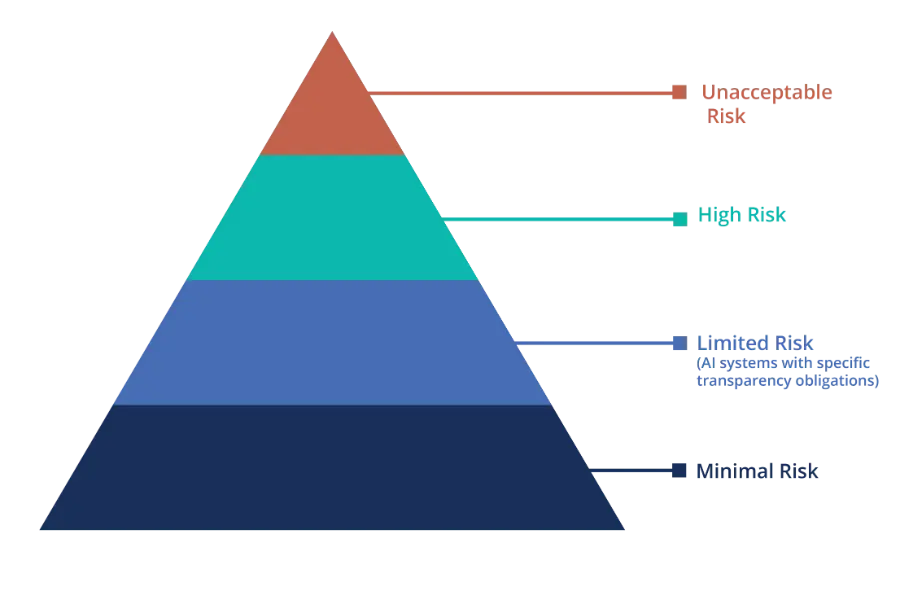

The risk-based classification of AIA

“I’d say this is the optimal strategy for regulatory bodies to take when determining requirements, as attempting to scope regulations in other facets will place an undue burden on providers of models that do not ultimately pose enough risk to make it worthwhile. ”

Ortal Shimon, account executive at Hi-Touch PR

The EU’s Artificial Intelligence Act (AIA) reaches companies across all sectors that develop or distribute AI in the EU, along with those using AI systems that produce outputs affecting EU residents.

Several players in the EU’s AI value chains are impacted, including the definition of “AI system”. The definition of AI system was expanded to include any autonomous machine-based system that “infers, from the input it receives, how to generate outputs.” With the advent of generative AI, the act also applies to “general purpose AI models,” or GPAI models, that are key building blocks of AI systems with broad applications, such as DALL-E and OpenAI’s GPT-4.

Also read: Artificial Intelligence Act: World’s first global AI law passed in EU

On this basis, the EU has cleverly chosen to categorise and manage AI models based on potential risk, which allows for more nuanced and effective management of risk, focusing resources and scrutiny where they are most needed. Specifically, it takes a risk-based approach, assigning AI systems to a risk class and requiring high-risk systems to meet stricter requirements than AI systems in a low-risk class.

AIA sets out four risk levels for AI systems: unacceptable, high, limited, and minimal (or no) risk and its clear categorisation of AI systems is consistent with global risk management frameworks such as the NIST AI RMF and ISO 420001.

This clear categorisation of AI systems is consistent with global risk management frameworks such as the NIST AI RMF and ISO 420001 and increases transparency and accountability.

The evergreen question: innovation vs regulation

“I remember talking with another CEO in Berlin who made a half-joke that they use the same amount of time for following regulations as they do for creating things.”

Erik Severinghaus, founder and CEO of Bloomfilter

Balancing innovation and regulation is an issue that has been watched, discussed, and debated since AI legislation was on the agenda. The AIA’s pioneering classification of AI risks into four tiers based on human rights and safety benchmarks has also received opinions from critics, AI industry practitioners, and experts in politics and law.

On the positive side, this categorisation system provides flexibility and allows innovative developers to develop less risky AI technologies without placing unnecessary regulatory restrictions on them. This fosters creativity and encourages the advancement of AI applications in various fields.

The AIA focuses on high-risk AI systems, creating certain burdens and barriers to AI development and innovation. For large corporations, extensive compliance requirements can hinder further technology development and market expansion. However, high compliance thresholds can prevent more companies from entering the AI field and help form a monopoly. This also leads to difficulties for some small and medium-sized AI enterprises or research organisations to bear the corresponding compliance costs and risks.

But the truth is that innovation and regulation are not incompatible contradictions, because there is another important element involved, the user. Effective regulation requires apps to be transparent, which helps build public trust in AI and the companies that produce it, which is essential for widespread acceptance of the technology and its integration into everyday life. By emphasising transparency, the classification system addresses concerns about the opacity of AI systems and promotes greater accountability. This does more good than harm to the long-term development of AI technology.

This may be why critics are more likely to view the AIA in a relatively positive light, causing it to be very comprehensive, prioritising consumer protection, transparency, and accountability, which is critical to fostering trust in AI technology. But when it comes to subsequent implementation and revision, there is still a long way to go.

AI governance attempts in other countries

In addition to categorising AI risks into four levels based on human rights and security, the AIA has another relatively important innovation, that it has started the process of horizontal regulation of AI, before which AI regulation was generally vertical. Horizontal regulation is legal rules that apply to all sectors and applications, covering all areas and people. This is why the bill emphasises strict regulation while also focusing on regulatory innovation, such as encouraging countries to carry out ‘sandbox testing’ and providing more convenience and support to small and medium-sized enterprises.

In the UK, which has been affected by the withdrawal from the European Union, the legislation aims to promote innovation while ensuring that AI is used ethically and responsibly, promoting transparency, accountability and fairness in line with EU standards.

The U.K. Safety Institute, the U.K.’s recently established AI safety body, this month released a toolset, called Inspect, to test the safety of AI models aimed at enhancing AI safety by making it easier for industry, research organisations and academia to develop AI assessments. This behaviour is also consistent with the AIA’s risk classification requirements for AI models.

China has taken a more top-down approach, imposing stricter controls on the development and deployment of AI, particularly in terms of surveillance and data privacy. The Chinese government has launched a “New Generation Artificial Intelligence Development Plan,” which plays an important role in standardising and guiding AI development based on national priorities.

The U.S. dominates the AI space, with OpenAI releasing Sora, a powerful new text-to-video platform, and Google launching Gemini 1.5, its next-generation AI model that can absorb requests 30 times larger than its predecessor. The U.S. has a relatively liberal approach to regulating AI, focusing more on fostering innovation and maintaining technological leadership, with a focus on ethical frameworks and guidelines rather than binding laws.

U.S. President Joe Biden issued an executive order in October 2023 restricting developers of “the most powerful AI systems” from sharing their safety test results and other critical information with the government, citing national security risks. The U.S. has also recently introduced NIST AI RMF, designed to manage the risks associated with AI systems, reflecting the growing recognition in the U.S. regulatory environment of the importance of risk management, governance, and ethical use of AI technology.

Also read: UK Government Signs Up Tech Experts and Diplomats for Landmark AI Safety Summit

What both countries have in common is that they will start by regulating vertically AI-related technologies that are most likely to jeopardise people’s rights or social stability, such as deep fake technology. This is also targeting governance in a direction with a higher potential risk factor.

Pop quiz

In the European Union’s recently released artificial intelligence Act, AI systems are divided into what four categories according to potential risks?

A. Unacceptable risk

B. High risk

C. Limited resk

D. Moderate risk

E. Minimal (or no) risk

The correct answer is at the bottom of the article.

Solid self-regulation already functioned

Legislation is lagging, and that’s why corporate autonomy regulations and industry writing consensus are crucial in such a fast-developing phase.

Google has established its own AI Principles, which emphasise the importance of creating socially beneficial AI that adheres to high standards of safety and fairness. Meta has also been involved in discussions about governing AI systems, particularly in terms of balancing innovation with privacy and fairness in the distribution of content.

Microsoft has been vocal about responsible AI, developing tools to detect and counteract bias in AI algorithms and promoting transparency in AI systems. IMB develops a company-wide AI ethics policy through its AI Ethics Council, focusing on trust and transparency to align AI development with human-centred principles.

However, a personnel change at OpenAI at the end of 2023 raised additional questions about the effectiveness of self-regulation. The company’s CEO Sam Altman was fired by OpenAI’s nonprofit board of directors, which was concerned about Altman’s lack of caution in his actions and the dangers that AI could pose to society.

According to OpenAI’s filing with the IRS, by 2018 the company will no longer tout a commitment to “openly share our plans and capabilities”; by 2021, the company’s goal has become to “build general-purpose AI” that resonates with commercial productisation interests, rather than an open-ended, research-oriented mission to “advance digital intelligence.”

Supporters, led by Sam Altman himself, wanted to bring powerful new technologies to the public quickly while continuing to move toward true general-purpose AI. Although Altman received an olive branch from Microsoft shortly after his dismissal and was eventually rehired by OpenAI, several of the members who initially fired him resigned. But this provides an important lesson for future AI regulators: the possibility of meaningful self-regulation, especially through smart corporate forms, is a fantasy.

Also read: Exploring the OpenAI and Microsoft partnership

The power struggle within the company and the ultimate failure of the nonprofit’s board to maintain control over an increasingly commercialised company is a reminder that if society wants to slow down the rollout of this potentially epochal technology, maybe it’s going to have to do it the old-fashioned way: through top-down government regulation.

Looking ahead: how to resolve the gap between tech advancement and followed-up governance?

“Exploring global AI legislation is like tasting a complex wine; each country adds its unique flavour, and sometimes it’s hard to predict whether it’ll hit the palate just right or leave a bitter aftertaste.”

Erik Severinghaus, founder and CEO of Bloomfilter

Global consensus

A global consensus on AI regulation will take a long time to reach, just take AIA for an example. Release of the act is step one and the following implementation still has a long way to go. The way to build a global regulation on AI requires a joint effort of individuals, companies, organisations and countries.

On the one hand, if Europe’s rules are much stricter than elsewhere, where regulation is less stringent, it could make European companies less competitive in the world. On the other hand, if Europe’s regulatory industry creates a lot of conflict with self-regulation, it will become much harder to enforce.

The lack of globally agreed classification standards may also create the risk of regulatory arbitrage. Take AIA for an example, the EU established a whole set of enforcement systems and multi-level supervision and implementation mechanisms in line with the landing of the bill, including national regulators of EU member states, etc., which is an advantage that the EU can play compared to individual countries.

Combination of horizontal and vertical regulation

As AI technologies continue to evolve, future legislation will likely need to be even more dynamic and adaptive, possibly incorporating real-time risk assessments and more flexible regulatory mechanisms. The global landscape of AI regulation is dynamic and complex, and the EU AI Act is a significant step that could influence global standards.

In addition to the comprehensive and relatively universal horizontal regulation that countries and organisations will strive to introduce, there will also be more specific to individual industries, especially in life sciences and financial services.

Dynamic supervision

In the face of the rapid development of AI technology, the challenges faced are undoubtedly huge. Such as the way AIA is graded, some AI systems may evolve in ways that increase the level of risk after an initial assessment, which requires ongoing monitoring and re-evaluation to ensure that AI models remain appropriately classified.

In addition, the subsequent development of AI technology is likely to exceed the expectations of any government regulations and company guidelines, which not only have a high requirement for the technical vision of lawmakers but also require immediate adjustment, supplement and revision of relevant regulatory regulations.

The correct answer is a, b, c and e.