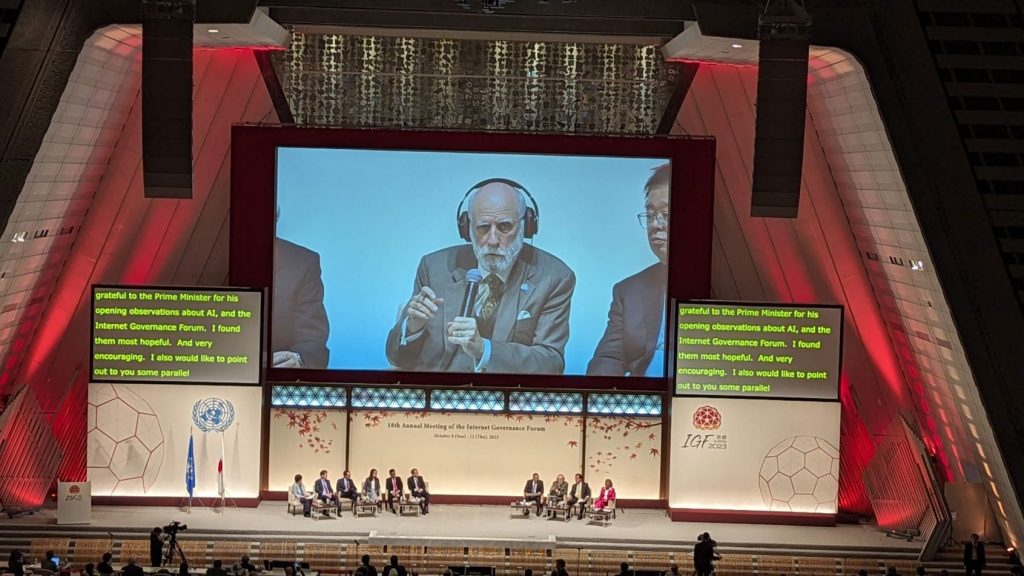

In a huge, multi-level conference centre overlooking a stylized lake against a verdant green mountain backdrop, thousands of delegates recently met in Kyoto, Japan, to discuss and consider the future of the Internet.

The five-day event was full of the usual phrases and soundbites you’d expect of a convention involving high-level politicians and corporate and organizational spokespeople – “multi-stakeholder engagement”, “collaboration”, “privacy, security and safety” were some of the most frequently uttered terms. But some sessions peeled back the uninspired jargon to reveal two weighty realities. First, Artificial Intelligence (AI), arguably the most powerful technological development the world has ever seen, is a formidable force for good, and it would be an even more formidable foe. Developments here must ensure humanity owns and controls AI, and we should never allow that relationship to flip. Second, data collection, flow and sharing, particularly across international borders, offers similar opportunities for dramatic progress, particularly when combined with AI, but also comes with threats.

To illustrate:

Every time an earthquake strikes, let’s say, Japan, it provides huge amounts of data that can be analysed using AI models to try to predict future earthquakes and ensure the next one is less harmful and lives are saved. If that data is shared across international borders, Japan’s earthquake data could help save lives in other countries too, and vice versa. But AI’s ability to ‘hallucinate’ – make things up – is well documented already, and a false prediction of an imminent disaster, particularly if it includes evacuation commands, could be incredibly disruptive and potentially harmful. Plus, the data used to feed the AI needs to be accurate, trustworthy and free of privacy and cybersecurity concerns, and, on a more political level, it needs to be usable by both technically advanced societies and developing societies. There are risks, for example, that advanced countries could take and use data from other countries without then sharing the information gleaned by AI analysis of that data.

“Data is the lifeblood of many economies today,” said Taro Kono, Japan’s Minister for Digital Transformation and Reform, in one of the opening sessions. “But it is fragmented, governance is fragmented, policy-makers are not always aware of the emerging technology that can help and the general public needs to understand the threats around disinformation and data accuracy.”

Also Read: China Unveils Stricter Regulations for AI Training Data

How AI and data helped during COVID

The benefits of this kind of AI-data combo were best seen during the development of COVID-19 vaccines. “COVID showed how important data is to unlock health innovations,” said Microsoft’s chief digital safety officer, Courtney Gregoire. “Good data creates better ideas, better productivity and helps everyone. But citizens must feel that their data is secure and protected, so we need trusted mechanisms for data transfer.”

Moderna and Pfizer were able to create their COVID vaccines in rapid time and also distribute them far more effectively using AI methods. As protracted as the pandemic felt, it would have been a lot worse without the AI developments and data sharing protocols that allowed a worldwide vaccination programme to be carried out.

Developments like DHIS2 from the University of Oslo will also help with future healthcare initiatives and outbreaks. It’s an open-source health management information system that is already in use in 100 countries that have agreed to share their data on the system.

And the Data Free Flow with Trust (DFFT) initiative, established by Japan in 2019, will bring together people from government, academia, the private sector and civil society (NGOs, consumer organisations) to try to bridge some of the gaps that exist currently in the guidelines (where they exist at all) for data provision and use.

Also Read: Worldcoin’s Value Plummets by 50% Amid Escalating Data Privacy Concerns

AI bias and how to solve it

Along with the incredible gains to be made using global data and AI, there are weaknesses, at least currently. Small defects in the data can be exacerbated by the machine. “Bias in AI is very real,” said Ivana Bartoletti, global chief privacy officer at Wipro. “We know AI shows lesser paid jobs to women, for example, and so automated decision-making and these biases will affect lives.”

The trouble is not only a technological one, however, as AI models are always trained on existing data and information, which is shaped by humans. “These issues can be addressed from a technical standpoint, but the problem runs deeper,” Bartoletti added. “It is rooted in society.”

The Hiroshima Process hopes to tackle this imminently. Created at the G7 summit in Hiroshima earlier in 2023, the “G7 Hiroshima Process on Generative Artificial Intelligence” hopes to provide a code of conduct as well as issues to be aware of, for anyone using generative AI models. The final report will be submitted before the end of 2023.

Misinformation and disinformation in generative AI

One of the biggest concerns around generative AI is of course the production and proliferation of ‘false news’ – images, videos and stories that appear to document reality, but are fictions, and are often created for nefarious purposes. “Technology has hacked our biology to bypass our rational minds as the various platforms compete for our attention,” said Maria Ressa, CEO and founder of Rappler, and Nobel Peace Prize winner in 2021. “Seventy percent of the world is now under authoritarian rule, and the social media platforms continue to deny, deflect and delay. We must move faster. This is a cultural moment for the world.”

Also Read: Deep Fake of Mr Beast Selling iPhones for $2 Goes Viral on Tiktok

Ressa pointed out that “lies spread six times faster than the truth”, a statistic discovered by the MIT Media Lab, and explained by the fact that falsehoods are nearly always designed to tap our emotional responses, while dry facts do not.

Meta’s president of global affairs, Nick Clegg, pointed to work they are doing, using AI itself to combat the negatives of generative AI. “Hate speech on Facebook occurs at the rate of around 0.01% to 0.02%, so for every 10,000 posts you scroll through, one or two could be considered harmful. And that is down by 60% over the last 18 months, thanks to our use of AI to combat it. So we are using AI as a tool to minimize the bad and amplify the good.”

Google’s president for global affairs, Kent Walker, also highlighted the work Google was doing, such as with SynthID, which attempts to detect AI-generated content and mark it as such, and the Secure AI Framework (SAIF), which aims to reduce risks when implementing and using AI models, particularly around data. “Identifying images and videos at a pixel level so we can authenticate where they came from, labelling of AI images in election ads – it’s all designed to understand the underlying meaning of the content, to determine what we can and cannot trust,” he said.

That word “trust” was how the four-day meeting started, and it is apt that it recurred again and again. Maria Ressa was particularly adamant that trust is core to the problems, and opportunities, AI brings, and that it all starts with the accuracy of the data the AI is trained on. “Without facts you don’t have truth, and without truth you don’t have trust, and without all three you don’t have freedom or democracy.”

Given that generative AI can create “a tsunami of information instantly”, to quote Tatsuhiko Yamamoto, professor at Keio University Law School, any work that can help to alleviate the epidemic of false news is worthwhile.