- Introduction

- What RIRs are and how they operate

- How policy consensus limits enforcement

- A table of enforcement realities

- Legacy resource challenges and contractual limits

- Why RIRs cannot act like regulators

- How enforcement constraints shape practical outcomes

- Perspectives on jurisdiction and accountability

- The enduring trade-off in internet governance

- FAQs

Introduction

Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) are central institutions in the internet’s addressing architecture. They manage and register IP address space allocations for regions that together encompass every connected network in the world. These organisations are crucial for preventing address duplication and ensuring that unique number resources are administered consistently so that the global routing system can function.

Yet for all their importance, RIRs do not have enforcement power of the sort that regulatory agencies wield when overseeing compliance with laws. They cannot impose fines, compel behaviour through legal authority, or seize resources in the way statutory regulators can. This limitation is structural, rooted in the historical evolution of internet governance, the voluntary and multistakeholder model these institutions embody, and the design choices that prioritised coordination over regulation. Understanding why RIRs lack enforcement power requires examining both how they operate and how they were designed to interact with the networks and organisations that depend on them.

Also Read: Why RIRs lack authority and how community sovereignty can undermine the internet

What RIRs are and how they operate

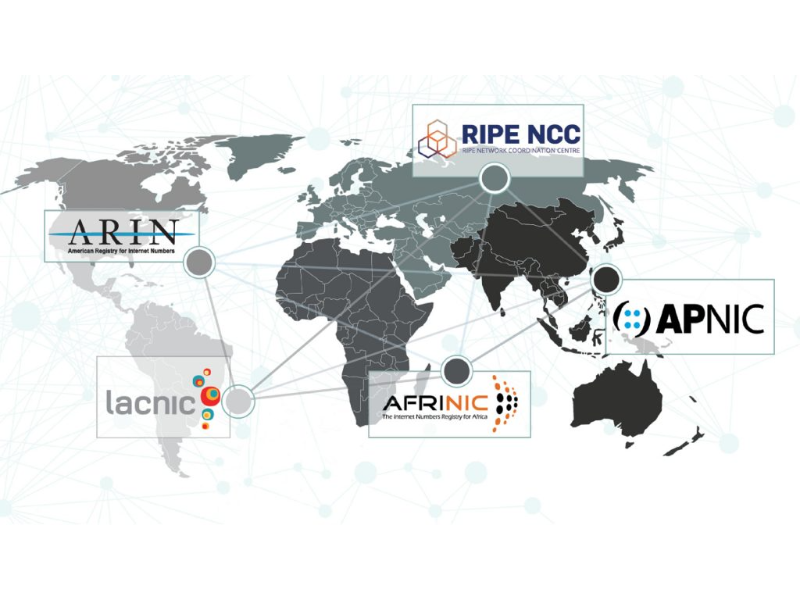

Regional Internet Registries emerged in the early 1990s out of practical necessity. As the internet expanded beyond academic and research networks into widespread commercial use, the need for regional coordination of address allocations became clear. Five RIRs were established — ARIN, RIPE NCC, APNIC, LACNIC and AFRINIC — each responsible for a geographic region. Their primary duty is to allocate and register IP address blocks and Autonomous System Numbers, ensuring that number resources remain unique and globally routable.

Unlike government regulators, RIRs are not empowered by statute nor backed by sovereign enforcement mechanisms. They are nonprofit, membership-based organisations whose policies are formulated through community-driven processes known as Regional Policy Development Processes (PDPs). These are bottom-up mechanisms where network operators, service providers, civil society stakeholders and technical experts debate, propose and adopt allocation and transfer policies relevant to their region.

This is not to say that RIRs have no authority at all — within their internal governance they have accountability mechanisms, bylaws, and contractual terms that bind members who agree to adhere to policy. But this authority exists in a contractual and organisational context, not as legal jurisdiction backed by statute.

Also Read: Why RIRs don’t have power to enforce internet address policies

How policy consensus limits enforcement

One of the clearest ways to see the limits of enforcement is through the nature of RIR policy development itself. Policy proposals must garner broad support within the community to be adopted. This process prioritises consensus, inclusivity and technical validity, often because it must account for diverse needs within regions and among stakeholders.

The result is a governance model that emphasises participation and coordination over command and control. Policies reflect negotiated community values, not legal mandates, and enforcement depends on willing compliance by members and participants rather than on legal or judicial authority.

As Lu Heng, founder of LARUS Limited, has argued, this voluntary foundation is fundamental to how RIRs function:

——Lu Heng, CEO at Cloud Innovation, CEO at LARUS Ltd, Founder of LARUS Foundation.

Heng’s analysis emphasises a structural truth: RIR policies are internal agreements among willing participants, not enforceable statutes. The strongest action an RIR can take is to refuse to provide further services, and even that action depends on continued cooperation by the broader community. This contrasts starkly with regulatory regimes where authorities can impose legal penalties.

Also Read: Lu Heng: IPv4 market shifts were inevitable, not about winning

A table of enforcement realities

To clarify where RIR authority stops compared to typical regulatory bodies, the following table summarises key differences in enforcement capabilities:

| Enforcement capability | Typical regulator | RIR reality |

|---|---|---|

| Impose fines or penalties | Yes | No |

| Compel behaviour through law | Yes | No |

| Seize assets | Yes | No |

| Withhold administrative services | Limited | Yes (e.g., refuse future allocations) |

| Influence routing or operational behaviour | Indirect | Indirect (through registry records and community norms) |

This comparison illustrates a simple point: RIR enforcement relies almost entirely on cooperation and indirect influence, not on legal authority.

Legacy resource challenges and contractual limits

The limitations of enforcement are even more visible when considering legacy IPv4 address allocations. These are address blocks assigned before the establishment of RIRs. Legacy holders often never signed formal contracts with RIRs and therefore are not bound by RIR policies in the first place. Data compiled in historical governance research indicates that a substantial portion of IPv4 allocations predates RIR systems, and many such holders have not entered into “Legacy Registry Service Agreements” with RIRs. As a result, RIRs lack legal authority to recover these resources or regulate their behaviour unless holders voluntarily choose to sign agreements.

This structural situation reinforces the point that RIR governance is transactional and consensual, not hierarchical and enforceable. Even when policies exist, enforcement is limited by the absence of legal mechanisms to bind all participants.

Also Read: How IPv4 asset strategy supports long-term enterprise growth

Why RIRs cannot act like regulators

Internet governance scholars have long noted the contrast between the private, multistakeholder model of RIRs and traditional statutory regulators. Milton L. Mueller, a long-standing scholar on the politics of internet governance, has explained that bodies like the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) themselves have limited enforcement powers, underscoring a wider pattern in internet governance:

“The ITU has no enforcement powers, which is one of the reasons why the idea that the ITU can somehow take over the Internet is strange. Because if the treaty does something fundamentally inimical to what [governments] want done with the Internet, they would simply not ratify it.”

——Milton L. Mueller, Professor and Program Director, Masters of Science in Cybersecurity Policy

Mueller’s observation, while made in the context of another organisation, holds for RIRs as well: global internet governance often lacks centralised enforcement mechanisms because participants remain sovereign entities with discretion about what to ratify or adopt.

This multistakeholder approach was chosen deliberately. Early internet architects prioritised technical coordination and interoperability over centralised regulation because they believed that rigid statutory enforcement could fragment the global network and stifle innovation. Over time, this design choice became institutionalised into the policy frameworks that guide RIR operations today.

Also Read: Case study: How enterprises generate recurring income from IPv4

How enforcement constraints shape practical outcomes

The absence of statutory enforcement power has real operational consequences. For example, when address transfer policies are updated, compliance depends on members’ willingness to adhere and on community norms rather than legal mandate. Transfer procedures vary in complexity and efficiency across regions, and enforcement of “needs tests” or documentation requirements depends on administrative processes rather than judicial enforcement.

Similarly, RIRs cannot force the return of unused address space. Policies often encourage return, but without legal mechanisms, organisations that hold large blocks of unused addresses have little incentive to relinquish them, particularly when doing so incurs administrative or opportunity costs.

These outcomes are not necessarily dysfunctional, but they reflect a governance model where compliance is shaped by practical incentives and community expectations rather than by legal coercion.

Perspectives on jurisdiction and accountability

Another nuance is jurisdiction. Because RIRs are private organisations based in specific countries, they are subject to the legal frameworks of those jurisdictions. Yet the resources they administer — IP addresses — are used globally. This creates a kind of jurisdictional overflow, where the legal environment of an RIR’s host country can influence operations without granting global enforcement authority over all resource holders or users.

Accountability mechanisms within RIRs focus on membership obligations, transparency of processes, and internal dispute resolution, but do not provide avenues for statutory enforcement against non-compliant entities beyond the membership contracts.

The enduring trade-off in internet governance

The choice to craft RIRs as voluntary, consensus-driven entities rather than sovereign regulators was consistent with early internet governance ideals. These ideals valued interoperability, decentralisation and technical coordination. For many years, this model worked effectively to ensure that global number resources supported the internet’s expansion without fragmentation.

However, as the internet became critical to commerce, security and national infrastructure, the limitations of a non-enforceable governance model have become more visible. The rise of address markets, address scarcity, and geopolitical tensions over infrastructure have all put pressure on a system designed for a different era.

Yet these pressures do not translate automatically into enforcement authority. To gain statutory enforcement powers, RIRs would require fundamental changes to international agreements or the establishment of new legal frameworks — changes that would reshape global internet governance beyond the RIR system itself.

FAQs

1. Do RIR policies have legal force?

RIR policies do not have legal force in the statutory sense. They are not created or enforced by governments or courts, but through community-driven policy processes within each registry. Their authority comes from agreement rather than law. In practice, policies apply through contracts. Organisations that sign service agreements with an RIR agree to follow current and future policies. For those without such agreements, especially legacy address holders, RIR policies are not binding.

2. Why can’t RIRs force organisations to return unused IP addresses?

RIRs do not own IP address space and lack legal authority to compel its return. Their role is to coordinate and register addresses, not to exercise property rights over them. While policies may encourage efficient use or return of unused space, compliance is voluntary. This is particularly true for legacy address holders who never entered into contractual relationships with RIRs and therefore are not subject to policy enforcement.

3. What happens if an organisation violates RIR policy?

When policies are violated, RIRs can take administrative actions such as denying future allocations, suspending services or requiring registry data corrections. They cannot impose fines or legal penalties. The most meaningful consequences are often indirect. Inaccurate or disputed address records can affect routing trust, peering relationships and an organisation’s standing within the broader internet ecosystem.

4. Could governments give RIRs enforcement power?

In theory, governments could attempt to grant enforcement authority through law or treaties. In practice, this would be difficult due to jurisdictional limits and the global nature of RIR operations. Such a move could also undermine the neutrality and broad acceptance of RIRs, potentially encouraging fragmentation and weakening the multistakeholder model that currently supports global coordination.

5. Does the lack of enforcement power make RIRs ineffective?

Not necessarily. RIRs have been effective at maintaining global address uniqueness and routability through voluntary coordination and shared incentives. However, as IP addresses become more economically and strategically significant, the limits of a non-enforceable governance model become more visible. These tensions reflect the system’s original design assumptions rather than outright failure.