- Introduction

- What RIRs are — coordination without authority

- Why RIRs lack enforcement power

- How scarcity emerged and why enforcement mattered

- Markets and digital assetisation

- A comparison of power and enforcement

- Legacy allocations and institutional imbalance

- Operational consequences for enterprises

- Governance, accountability and transparency

- IPv6, scarcity persistence and future directions

- Conclusion

- FAQs

Introduction

The internet’s functioning depends on a set of indispensable numerical identifiers known as Internet Protocol (IP) addresses. For decades, these identifiers — specifically IPv4 addresses — were treated primarily as technical enablers of connectivity. Over time, however, the exhaustion of freely allocable IPv4 space transformed them into assets with economic and strategic value. In parallel, the institutions that coordinate their allocation — the Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) — have never possessed enforcement power in the legal sense.

This combination of scarcity and institutional powerlessness has shaped how IPv4 addresses are managed, traded and interpreted as digital assets. Enterprises treat address blocks as balance-sheet resources and participate in transfer markets. Yet RIRs remain administrative coordinators without the capacity to compel behaviour through law, penalties or compulsory compliance. This dynamic has direct implications for scarcity, allocation, legitimacy and long-term digital asset management practices.

Understanding these implications requires examining why RIRs lack enforcement power, how that limitation interacts with IPv4 scarcity, and what it means for enterprises holding or trading address space.

Also Read: Why RIRs lack enforcement power

What RIRs are — coordination without authority

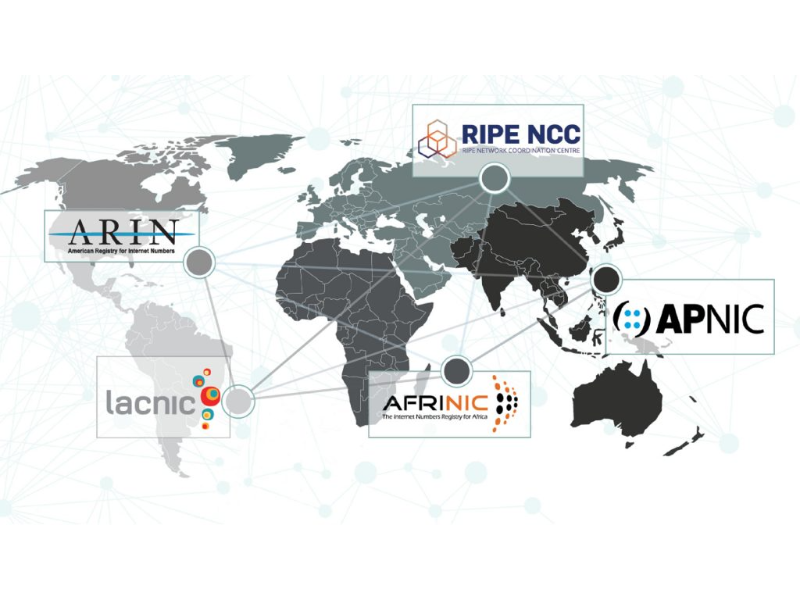

Regional Internet Registries emerged in the early 1990s as part of a distributed, multistakeholder architecture for managing Internet number resources. Unlike traditional regulators, RIRs are non-profit, membership-based organisations responsible for allocating blocks of IP addresses and maintaining registration databases. There are five such registries — ARIN, RIPE NCC, APNIC, LACNIC and AFRINIC — each serving large geographic regions.

Their mandate is coordination: ensuring globally unique address assignments and supporting scalable routing. Policies are developed through bottom-up, consensus-based processes involving network operators, service providers and other stakeholders. Unlike statutory regulators, RIRs do not derive authority from governments or legal jurisdictions; rather, they operate through community recognition, contractual terms and shared incentives. This distinction is crucial because it reveals the difference between coordination and enforcement.

Also Read: Rethinking digital control: Why the idea of sovereignty in cyberspace is a fallacy

Why RIRs lack enforcement power

RIRs do not have enforcement authority because they were never designed as regulators or sovereign entities. They do not possess legal jurisdiction, cannot impose fines or penalties, and lack the statutory mandate to compel compliance. Their authority is contractual and technical, not legal.

A recent analysis by Lu Heng, who has worked across internet governance and number resource communities, underscores this structural reality:

Heng’s framing highlights that RIRs operate in a domain where participants can choose cooperation or exit, a condition fundamentally incompatible with coercive authority. This structural design choice was intentional, rooted in early internet governance ideals that prioritised interoperability and decentralisation over regulation.

Also Read: Case study: How enterprises generate recurring income from IPv4

How scarcity emerged and why enforcement mattered

IPv4 address exhaustion was not a surprise. The original protocol specified approximately 4.3 billion unique addresses. As internet use expanded globally, these addresses were allocated faster than anticipated. Over time, free pools at global and regional levels were depleted.

With scarcity came the need to manage limited resources sustainably. However, RIRs could not compel redistribution or reclaim unused legacy allocations because they lacked legal authority. Instead, policies encouraged efficient use and voluntary returns, but without enforcement tools, these measures had limited impact. Large legacy holders — organisations that received blocks before RIR systems existed — still control significant share without contractual obligations to comply with contemporary policy.

In this environment, scarcity did not prompt regulatory enforcement; it produced markets and new forms of asset valuation.

Markets and digital assetisation

IPv4 addresses increasingly behave like digital assets. They have price signals, transfer mechanisms and brokers, and they often appear in enterprise due diligence and mergers. Yet their legal status remains ambiguous: while registry contracts grant usage rights, they do not define statutory ownership or enforceable property rights.

Markets have arisen to fill the governance gap. Instead of top-down allocation or reclamation through coercion, addresses move through negotiated transfers between holders. These markets provide a decentralised, voluntary mechanism for rebalancing resource distribution. They do not, however, erase the structural limitation: RIRs can only record transfers and enforce internal policy conditions, not enforce market outcomes through legal sanction.

Milton L. Mueller, a long-time scholar of internet governance, has observed that governance bodies such as RIRs and others in the ecosystem rely on voluntary cooperation rather than enforcement:

“The internet’s governance bodies function because participants choose to follow the rules. They were not given coercive power, and that was intentional. The trade-off is that economic and political pressures eventually test those assumptions.”

——Milton L. Mueller, Professor and Program Director, Masters of Science in Cybersecurity Policy

Mueller’s perspective situates the RIR model within a broader governance philosophy. The absence of enforcement power is not an accident but a consequence of historical design choices intended to preserve global interoperability and decentralised control.

A comparison of power and enforcement

The difference between a statutory regulator and an RIR is stark:

| Feature | Statutory regulator | RIR |

|---|---|---|

| Legal authority | Yes | No |

| Ability to impose fines | Yes | No |

| Enforce through courts | Yes | No |

| Administrative enforcement | Yes | Limited (deny services) |

| Contractual leverage | Limited | Yes (only where agreements exist) |

| Market influence | Indirect | Through records and policy |

This table illustrates why scarcity is mediated by markets and cooperation rather than legal enforcement.

Also Read: How IPv4 asset strategy supports long-term enterprise growth

Legacy allocations and institutional imbalance

Legacy IPv4 allocations — those made before RIRs formalised contractual frameworks — remain an enduring source of imbalance. Holders of these blocks are not bound by contemporary policies because they did not sign service agreements. As a result, RIRs lack the legal basis to demand compliance or recovery of these addresses, even when unused. This reinforces scarcity and centralises control among early recipients, while later entrants navigate transfer markets to acquire space.

Operational consequences for enterprises

For enterprises that depend on global reach, IPv4 scarcity and RIR powerlessness has several practical effects:

- Asset planning and valuation: IPv4 addresses are treated as intangible assets with market value, influencing company valuations and capital decisions.

- Operational continuity: Legacy addresses and non-enforceable policies mean enterprises must manage risk without assurance of regulatory-backed rights.

Governance, accountability and transparency

Despite limited enforcement power, RIRs operate with a high degree of transparency and community accountability. Policies are debated openly, boards are elected, and financial reports are public. According to an analysis of RIR governance frameworks, accountability and transparency are central objectives, even in the absence of legal enforcement.

However, this accountability operates within a consensus-driven, voluntary environment, which distinguishes it sharply from enforcement regimes that rely on legal authority.

Also Read: Lu Heng: IPv4 market shifts were inevitable, not about winning

IPv6, scarcity persistence and future directions

IPv6 was designed to overcome IPv4 scarcity by providing a vastly larger address space. Despite the technical viability of IPv6, adoption remains incomplete and uneven. IPv4 remains widely used due to legacy systems, compatibility requirements and slow migration paths. As long as IPv4 continues to be required for interoperability, scarcity and the limitations of RIR enforcement will persist, shaping asset management and market dynamics.

Conclusion

The powerlessness of RIRs in enforcement terms is not a flaw but an inherent feature of their design and history. They function as coordinators rather than enforcers, which enabled rapid global growth without centralised control. However, the rise of IPv4 scarcity as an economic condition and the treatment of addresses as digital assets have exposed the limitations of a governance model grounded in voluntary cooperation.

Understanding these structural realities helps clarify why scarcity has been managed through markets and social norms rather than regulatory compulsion. It also illuminates the conditions under which enterprises navigate digital asset management in an environment where authority is procedural, not statutory.

FAQs

1. Why can’t RIRs enforce IPv4 redistribution?

RIRs cannot enforce redistribution because they were never established as statutory regulators with legal authority over IP address space. Their mandate is limited to coordination, record keeping and policy development through community consensus. They do not own IPv4 addresses, nor do they have the power to reclaim resources through legal compulsion. Any enforcement action would require backing from national or international law, which does not exist in the current governance model. As a result, RIRs rely on voluntary compliance, contractual relationships and community norms, which are effective for coordination but insufficient for enforcing redistribution in a scarce and economically valuable environment.

2. Does IPv4 scarcity mean the RIR system has failed?

IPv4 scarcity does not indicate a failure of the RIR system, but rather the limits of what it was designed to do. RIRs were created to manage uniqueness and stability, not to guarantee perpetual abundance. The exhaustion of IPv4 space was anticipated decades ago, and the system successfully delayed fragmentation while enabling global growth. Scarcity emerged because the address pool is finite and early allocations were generous by today’s standards. The RIR system continues to function as intended by maintaining accurate registries and supporting transfers, even though it cannot correct historical imbalances or override market dynamics.

3. Are IPv4 addresses legally owned digital assets?

IPv4 addresses occupy an unusual position in law and practice. Most RIRs explicitly state that IP addresses are not property and that registrants receive usage rights rather than ownership. However, in practice, IPv4 addresses behave like assets: they can be transferred, valued, and recorded in financial statements. This disconnect creates legal ambiguity. Control over addresses is recognised through registry records and routing acceptance, not through statutory ownership. As a result, enterprises manage IPv4 holdings as digital assets operationally, while remaining exposed to legal uncertainty should governance rules or recognition frameworks change in the future.

4. Why hasn’t IPv6 eliminated the problem of IPv4 scarcity?

IPv6 was designed to provide an effectively unlimited address space, but adoption has been uneven across regions, industries and networks. Many legacy systems, applications and customer environments still rely on IPv4, creating operational dependencies that are costly and complex to unwind. Dual-stack deployments and translation mechanisms add expense and risk, encouraging continued IPv4 usage even as scarcity worsens. As long as IPv4 remains necessary for interoperability, demand persists. This ongoing reliance means that IPv6 complements rather than replaces IPv4, leaving scarcity unresolved and reinforcing the importance of address markets and asset management strategies.

5. Could RIRs realistically gain enforcement power in the future?

Granting RIRs enforcement power would require a fundamental shift in global internet governance. It would likely involve new international agreements, legal mandates or the integration of RIR functions into state-backed regulatory frameworks. Such changes would raise complex questions about jurisdiction, sovereignty and political influence, potentially undermining the neutrality that has historically supported global coordination. While some policymakers discuss stronger oversight of digital infrastructure, there is no clear consensus on empowering RIRs directly. For now, the system remains intentionally non-coercive, with coordination prioritised over enforcement to preserve interoperability and global trust.