- Video and sign-in records suggest ICANN’s lawyer entered AFRINIC premises without the Official Receiver’s knowledge during a weekend absence.

- Such an act may breach Mauritian law and AFRINIC’s governance rules, raising serious concerns about oversight and legal propriety.

On January 11, 2025, a lawyer named Dooshyant Jhurry from the Mauritian firm Legis And Partners, representing ICANN, visited the AFRINIC building, the internet registry for Africa, to retrieve a document.

We don’t know what that document was nor why he needed to retrieve it on a Saturday morning. We do know that the Official Receiver for AFRINIC, Gowtamsingh Dabee, who was charged with supervising AFRINIC’s election arrangements, and acting as a stand-in executive until a board and CEO could be reconvened, was absent, on vacation.

We also know that performing these kinds of legal activities, on a weekend, without informing the Receiver and while he is not in the country, is at the very least improper, and at worst an unlawful attempt to sidestep due process.

Why would ICANN’s lawyer in Mauritius do this? What was in that document? Why try to retrieve it behind the Official Receiver’s back?

ICANN told BTW Media: “ICANN has been clear and transparent about the fact that it offered the Official Receiver neutral and independent assistance upon his request and within his role. The statement that our external counsel called at AFRINIC’s premises on 11 January 2025 to retrieve a document is categorically false and erroneous. He did not visit AFRINIC’s premises on that date.”

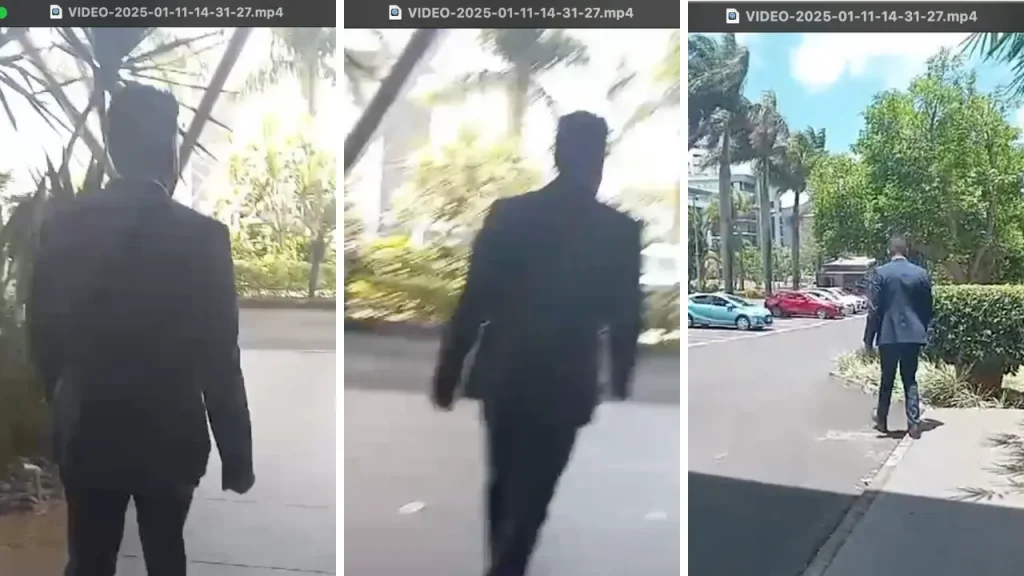

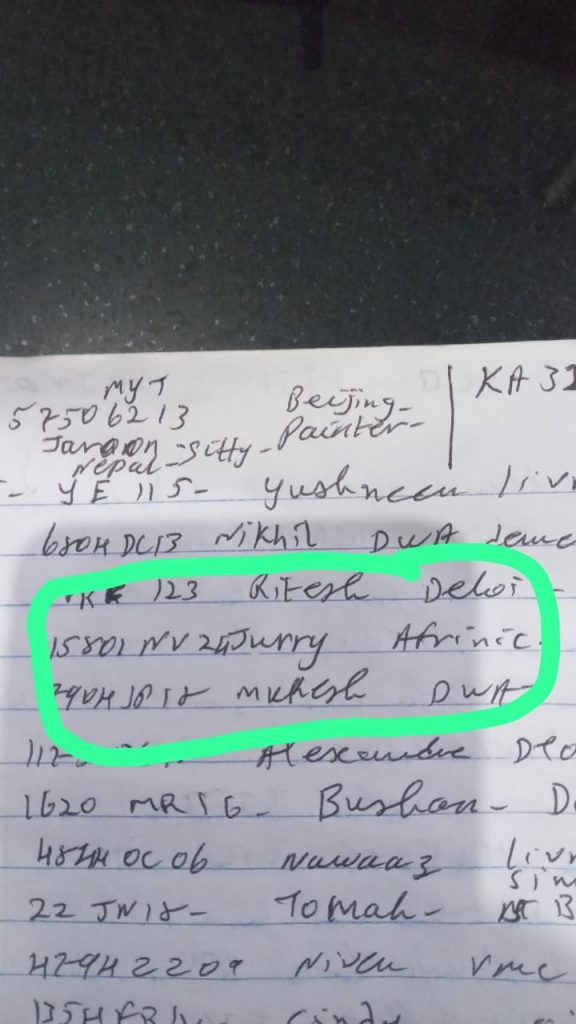

BTW Media has seen time-stamped video of a person that resembles Jhurry leaving AFRINIC premises on that date. We have also seen records of his vehicle registration signing in and out of AFRINIC premises on that day. The security guard working at AFRINIC on January 11 has also confirmed that a visit from a lawyer representing ICANN took place on that day.

BTW Media reached out to Legis And Partners asking the lawyer what his purpose was. We have not received a response.

Why might a lawyer visit AFRINIC without the official receiver’s knowledge?

There are few legitimate reasons a lawyer representing ICANN would need to physically retrieve a document from AFRINIC’s headquarters, particularly without the Official Receiver’s knowledge or oversight.

Under Mauritius’ Insolvency Act 2009, once a Receiver is appointed by the court, that Receiver becomes the sole legally empowered person to administer the company’s affairs, including control over property, records, and corporate decisions.

This means any action involving the retrieval of internal documentation would typically require the Receiver’s explicit consent or be carried out at his direction. Without this, the act risks being interpreted as trespass or unauthorized access to a court-supervised entity, as well as interference with the functions of a court-appointed officer, and a potential breach of court orders concerning the receivership.

So, why take this risk? If the retrieval was innocuous why not wait for the Receiver’s return? If it was urgent, why not notify him? The absence of transparency, paired with video evidence contradicting ICANN’s public statement, raises the possibility of intentional concealment.

If ICANN knew about this, it suggests illegal activity

If ICANN, as the client, authorized or even knew in advance that their lawyer was planning to access AFRINIC premises during the Official Receiver’s absence, this decision carries serious legal implications.

It suggests that a globally recognized internet governance body knowingly disregarded the legal authority of the Receiver as the acting executive, disregarded court orders that placed AFRINIC under formal receivership supervision, and disregarded the ethical boundaries of interacting with a legally controlled organization.

Depending on the document’s nature and its subsequent use, such an act could also constitute improper influence in AFRINIC’s governance process, and aiding and abetting an unauthorized action against a court-supervised entity.

More critically, if any action taken using that document later influenced AFRINIC’s election process, legal challenges could be raised questioning the validity of decisions made under the influence of improperly obtained materials.

If ICANN did not know about this, it suggests a lack of accountability

On the other hand, if ICANN genuinely had no knowledge of the visit, and it was carried out independently by its legal representatives, that raises a different set of questions about oversight and accountability.

How is it that a high-stakes legal matter concerning the governance of Africa’s only RIR could involve unsanctioned actions by counsel representing a key internet governance body?

Did ICANN’s internal governance break down? Does it not have clear protocols for how its legal agents operate in sensitive, jurisdiction-specific matters?

For an organization that prides itself on transparency and neutrality, this would represent a significant risk, and cast doubt on its ability to engage responsibly in international legal contexts.

It would also shift legal exposure onto the law firm and possibly the individual lawyer involved, who could face disciplinary consequences under Mauritian legal ethics rules if proven to have entered AFRINIC premises or handled documents without legal right or client instruction.

The timing and secrecy are hard to ignore

It is difficult to dismiss the implications of the timing; a Saturday morning visit during a period when the Receiver was out of the country, and with no record of official coordination or even notification.

This combination of factors suggests that whoever authorized the visit either did not want the Receiver to know, or believed it would be easier to retrieve the document without his oversight.

Either scenario implies a willingness to circumvent due process, which is especially concerning when AFRINIC is in a delicate legal and operational state.

Why this matters

AFRINIC is Africa’s steward of internet number resources, responsible for the digital infrastructure that powers everything from financial institutions to telecoms to civil society. The organization has been in a legal and governance crisis for more than three years, and its return to stability depends heavily on court supervision, transparent elections, and accountability from all stakeholders—including ICANN.

If ICANN’s representatives are undermining that process—knowingly or not—it threatens not only AFRINIC’s legitimacy but also Africa’s trust in global internet governance. Stakeholders across the continent, from governments to civil society, are watching this transition closely.

They deserve answers. And, if wrongdoing occurred, they deserve accountability.