- IPv4 exhaustion was a gradual, policy driven process rather than a sudden technical failure.

- Address scarcity reshaped internet governance, markets, and operator behaviour worldwide.

Early warnings and architectural limits

The exhaustion of IPv4 was not an unexpected crisis, but a structural outcome of early internet design choices. IPv4, defined in the early 1980s, allows for approximately 4.3 billion unique addresses. At the time, this seemed comfortably large. The internet was still an academic and government network, and address allocation followed a generous, class-based model.

By the early 1990s, engineers had begun to recognise that this abundance was illusory. Rapid commercialisation, the rise of personal computing, and the emergence of the World Wide Web accelerated address consumption. According to the Internet Assigned Numbers Authority, classful allocation wasted large blocks of addresses, prompting the introduction of Classless Inter-Domain Routing to slow depletion. These measures extended IPv4’s lifespan, but did not remove the underlying limit.

Also Read: What makes an IP address a form of digital capital

Regional exhaustion and policy responses

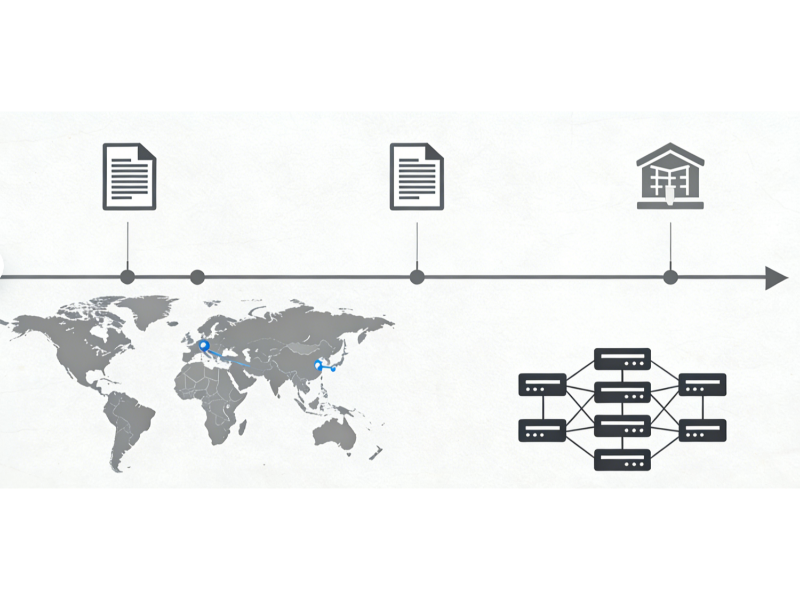

The transition from centralised allocation to Regional Internet Registries marked a shift in governance. Organisations such as ARIN, RIPE NCC, APNIC, LACNIC, and AFRINIC became responsible for distributing address space within defined regions. Their policies increasingly reflected scarcity rather than abundance.

Between 2011 and 2015, each RIR declared IPv4 exhaustion, beginning with APNIC in the Asia-Pacific region and followed by RIPE NCC, ARIN, LACNIC, and finally AFRINIC. Exhaustion did not mean addresses vanished, but that no new large blocks remained available. Operators were forced to adopt workarounds such as Network Address Translation or acquire addresses through transfers.

These developments raised questions about fairness and long-term sustainability. While transfer markets improved utilisation efficiency, critics argued that they favoured capital-rich organisations and distorted the original non-commercial principles of address allocation.

Also Read: IPv4: The digital real estate of the 21st century

Also Read: Why CFOs, not just CTOs, should care about their IP inventory

Case study: APNIC and early exhaustion

APNIC’s early exhaustion illustrates how regional growth patterns shaped outcomes. The Asia-Pacific region experienced rapid internet expansion driven by population growth, mobile adoption, and emerging digital economies. In 2011, APNIC reached its final IPv4 allocation phase, introducing strict rationing policies.

This forced many operators to accelerate IPv6 deployment sooner than their counterparts elsewhere. While often cited as a success story, the transition was uneven. Smaller operators struggled with costs and compatibility, while large networks adapted more easily. The experience highlights a recurring tension in internet governance: policy solutions may be technically sound, but economically asymmetric.

Conclusion

IPv4 exhaustion was not a single moment, but a decades-long process shaped by technical constraints, policy decisions, and uneven global growth. While it spurred innovation and governance reform, it also exposed structural inequalities that continue to influence how internet resources are managed today.