• Scammers are impersonating RIPE NCC to exploit members’ fear of losing IP address resources, highlighting misconceptions about the registry’s role.

• The incident reveals deeper structural misunderstandings about ownership and contractual relationships in internet number resource governance.

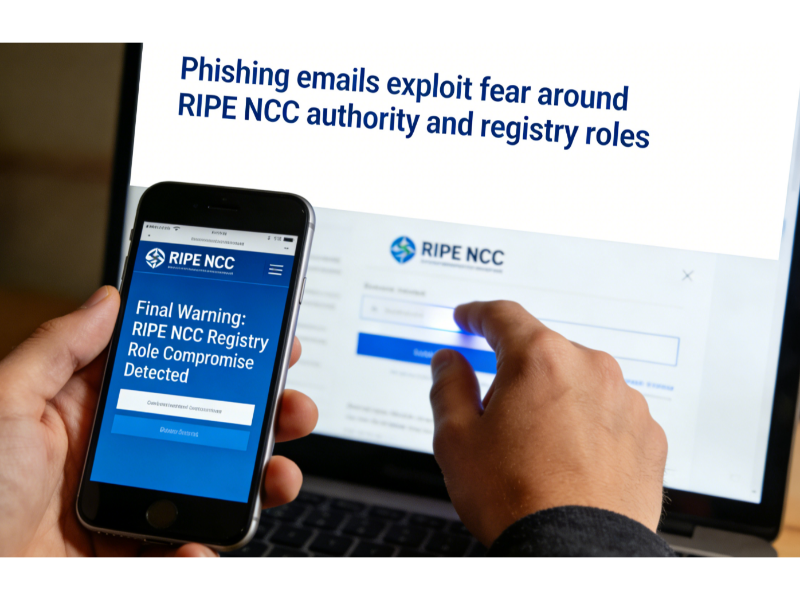

Phishing Exploits Registry Fear

Members of the Réseaux IP Européens Network Coordination Centre (RIPE NCC), the Regional Internet Registry (RIR) for Europe, the Middle East and parts of Central Asia, have recently been targeted by fake emails purporting to be official communications. These messages, including ones using subjects such as “Download Review,” demand urgent action to confirm technical data within a short timeframe. In fact, these emails

“did not come from RIPE NCC. It was a phishing attempt, exploiting fear—specifically, fear of RIPE NCC’s perceived authority.”

Security warnings from RIPE NCC itself confirm that phishing scams have circulated under different guises, such as a fake “Technical Information Verification” email and a bogus “Licence Information Verification” message, none of which originate from the registry’s official domain. Legitimate RIPE NCC announcements appear on certified channels and authenticated mailing lists only.

The success of these scams depends less on technical deception and more on psychological leverage. Many internet operators treat registry communications with heightened urgency for fear of losing critical resources such as IPv4 blocks or Autonomous System Numbers. As the commentary notes,

“many members subconsciously treat it as a regulator with sovereign power, capable of shutting down their entire business overnight.”

Registry Roles Versus Perceived Power

This misunderstanding touches on a broader issue: the nature of RIRs themselves. RIPE NCC and other registries such as ARIN and APNIC do not exercise legal authority over internet routes or sovereign control over address resources. Their role is administrative and contractual: they maintain databases that record address allocations and ensure uniqueness globally.

Scammers take advantage of the fact that many organisations misinterpret the registry’s procedural functions as having far greater legal force than they actually do. In reality, an RIR cannot unilaterally revoke an organisation’s address records without due process stipulated in policy and contract. Likewise, legitimate registry processes, such as data accuracy checks, are cooperative and scheduled with members rather than urgent and threatening.

While RIPE NCC has issued alerts urging members not to engage with unauthorised messages — emphasising that official emails are sent from the domain and that important communications appear in announce lists or on ripe.net — confusion persists among some stakeholders. Public security alerts routinely remind members to avoid clicking links or providing confidential information in response to suspicious claims. This raises the question of whether registry communication practices are sufficiently clear and proactive to counter sophisticated scams.

Also Read: IPv4 as an investment asset: upper potential

Also Read: How much do regional internet registries really cost and who pays?

Ownership, Policy and Structural Misunderstandings

The phishing incident has sparked renewed discussion about why fear around registry authority persists. One view suggests that the underlying issue is the way internet number resources are governed. Under current RIR policy frameworks, members do not own their IP addresses in a legal property sense; rather, they hold them under contractual agreements with the registry. This nuance matters because it shapes how organisations perceive risk and respond to official and unofficial communications alike.

Registry critics argue that stronger clarity — perhaps even reform in recognition of ownership rights — would reduce the psychological leverage scammers exploit. At a minimum, better education on the contractual and functional limits of RIR authority could reduce the impact of future scams.

For now, the incident serves as both a security warning and a reminder of how misunderstandings about governance roles can have real operational consequences for network operators, particularly smaller organisations that may feel exposed to regulatory or contractual penalties.