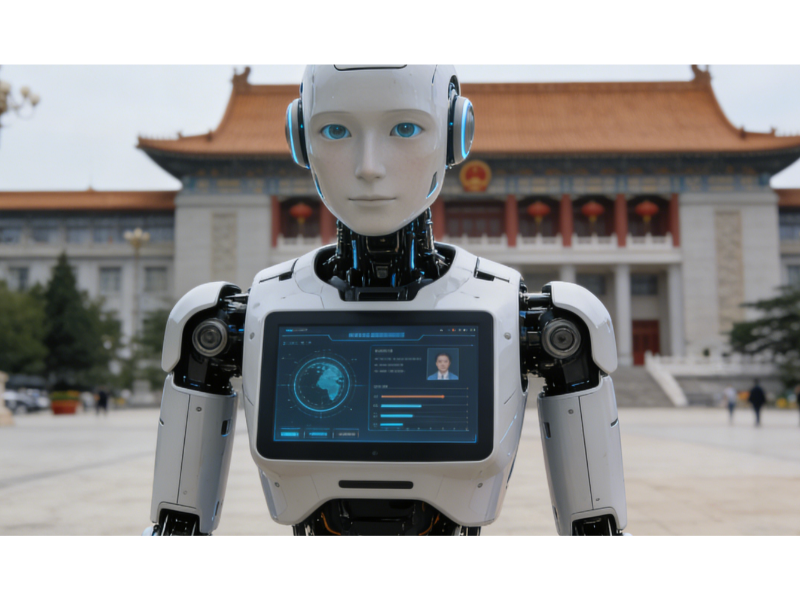

• China has released draft rules aimed at regulating artificial intelligence systems that simulate human interaction, expanding its oversight of generative AI.

• The proposals underline Beijing’s focus on social stability and information control, raising fresh questions for developers and foreign firms operating in China.

What happened: China has published draft regulations designed to govern artificial intelligence systems

The draft rules, released by the Cyberspace Administration of China, focus on AI services that can engage in natural language conversations, mimic emotional responses or otherwise appear to interact like a human. Under the proposals, providers would be required to ensure such systems uphold “core socialist values” and do not generate content that could endanger national security, social order or public morals.

Developers would also need to label AI-generated content clearly and put mechanisms in place to prevent users from becoming overly dependent on systems that simulate emotional or social interaction. The rules add to existing requirements that generative AI services undergo security assessments and register with authorities before being offered to the public.

The draft regulations are open for public feedback, a standard step in China’s rule-making process. They come as domestic technology companies race to deploy conversational AI tools in areas ranging from customer service to education and entertainment, while global firms monitor how China’s regulatory stance may affect cross-border cooperation.

China has already introduced measures covering recommendation algorithms and deepfake technologies. The new draft suggests regulators are paying closer attention to the psychological and social impact of AI systems that can blur the line between human and machine interaction.

Also Read: CAIGA rewrites Africa’s IP rules without its resource holders

Also Read: UK eases AI research rules to drive innovation

Why it’s important

The proposed rules highlight how China is carving out a distinct regulatory path for artificial intelligence, placing social governance and political control at the centre of technology oversight. For companies building chatbots, virtual companions or advanced assistants, compliance may require redesigning products to limit emotional cues or conversational depth.

Supporters of regulation argue that guardrails are needed to prevent manipulation, misinformation or unhealthy reliance on AI systems. However, the breadth of the language in the draft rules may create uncertainty for developers, particularly around how regulators will judge concepts such as “emotional dependence” or harmful influence.

The move also reflects intensifying global debate over how far governments should go in regulating AI that imitates human behaviour. While the European Union has focused on risk categories and transparency through its AI Act, China’s approach places heavier emphasis on content control and alignment with state priorities.

For international firms, the draft rules reinforce the challenges of operating AI services in China’s tightly regulated digital environment. Questions remain over whether strict oversight could slow innovation or push experimentation into less visible channels, even as authorities seek to balance growth with control.