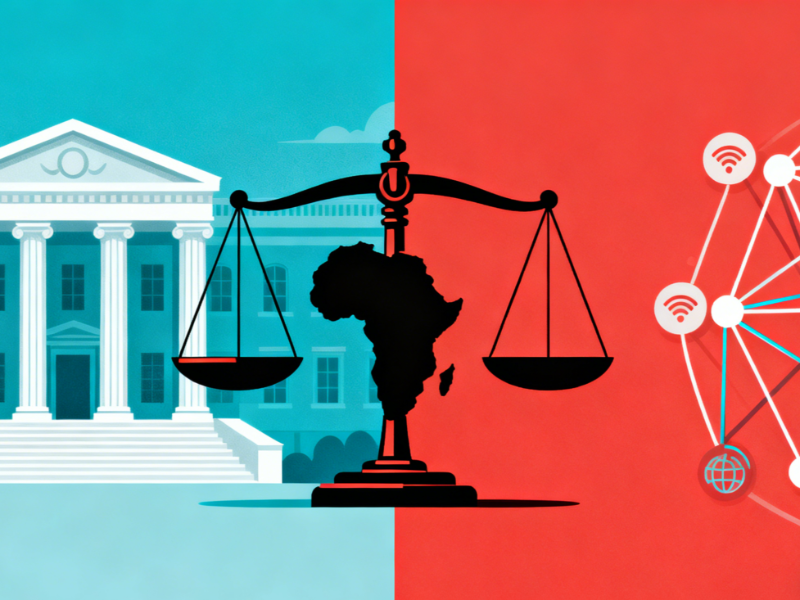

- Smart Africa leverages state power and continental coordination to influence AFRINIC reforms and internet policy.

- AFRINIC remains a Regional Internet Registry governed by its membership, using bottom-up processes for number resource allocation.

What is Smart Africa and why CAIGA matters

Smart Africa is a pan-African alliance of 40 governments and private-sector partners focused on accelerating digital transformation and strengthening continental infrastructure. Through a 2024 Memorandum of Understanding with ICANN, it has developed the Continental Africa Internet Governance Architecture (CAIGA)—a governance proposal that gives states a more formal, institutionalised role in AFRINIC reforms. Smart Africa argues that the AFRINIC crisis, including contested elections and institutional instability, threatens Africa’s “digital sovereignty” and requires a coordinated continental response. In a statement, Smart Africa cited years of legal and governance turbulence as central to its push for stronger oversight and stability.

Also Read: What Is Smart Africa’s CAIGA Initiative?

What AFRINIC is: A registry built by the community

By contrast, AFRINIC (the African Network Information Centre) is one of the five Regional Internet Registries (RIRs) that manage IP addresses, autonomous system numbers, and other internet-numbering resources. Governance at AFRINIC is designed to be bottom-up: members—including ISPs, operators and civil society—participate in policy development and decision-making. This structure emphasises technical independence and limits direct political influence over the registry’s operations. AFRINIC’s model has historically allowed communities to self-govern number resource allocation without state interference.

Also Read: CAIGA’s rise: What it means for AFRINIC members and operators

Key structural differences: CAIGA vs AFRINIC governance

The CAIGA proposal differs sharply from AFRINIC’s established governance mechanisms. Through CAIGA, Smart Africa envisions a Council of African Internet Governance Authorities and a permanent secretariat, potentially overseen by governments rather than solely by AFRINIC’s membership. Critics say this introduces a top-down layer of political endorsement—effectively allowing states to override or influence decisions that normally require community votes. According to Internet governance scholar Milton Mueller, “ICANN’s support for Smart Africa … risks undermining the multistakeholder model,” because CAIGA could place political power above community governance.

Meanwhile, technical community members such as Amin Dayekh argue that CAIGA establishes a “parallel authority structure” that bypasses AFRINIC’s existing channels. In his analysis, Dayekh warns that political and technical functions may merge under CAIGA, eroding the clarity and accountability that AFRINIC’s multistakeholder processes currently guarantee.

Risks, trust and data governance

Concerns about CAIGA go beyond structure. Smart Africa was criticised in 2025 for a data breach: it reportedly sent out an invitation to AFRINIC members via email, but by placing all addresses in the “to” field (instead of blind copy), exposed private contact information. This incident raised serious questions about how Smart Africa obtained and handled non-public AFRINIC member data—deepening suspicions about its influence and methods.

Why the difference matters for Africa

At the heart of the Smart Africa vs AFRINIC debate is a tension between political legitimacy and technical neutrality. Smart Africa sees CAIGA as a way to unify African states, ensure reforms, and safeguard internet resources under continental leadership. AFRINIC’s defenders argue that turning governance into a more political process risks undermining its technical function, threatening trust in address allocation, and potentially fragmenting resource management. If CAIGA’s model prevails, it may reshape how Africa—and possibly other regions—govern their internet infrastructure.

Smart Africa and AFRINIC represent two very different visions for Africa’s internet: one rooted in political coordination, the other in member-led technical sovereignty. The future of Africa’s internet governance depends on whether these differing approaches can co-exist—and which principles of legitimacy ultimately guide reform.