- The internet was born out of a US Defense Department need to share expensive computing resources and accelerate AI research.

- Commercial interest at a 1988 trade show, not academic adoption, was the true sign of its global potential.

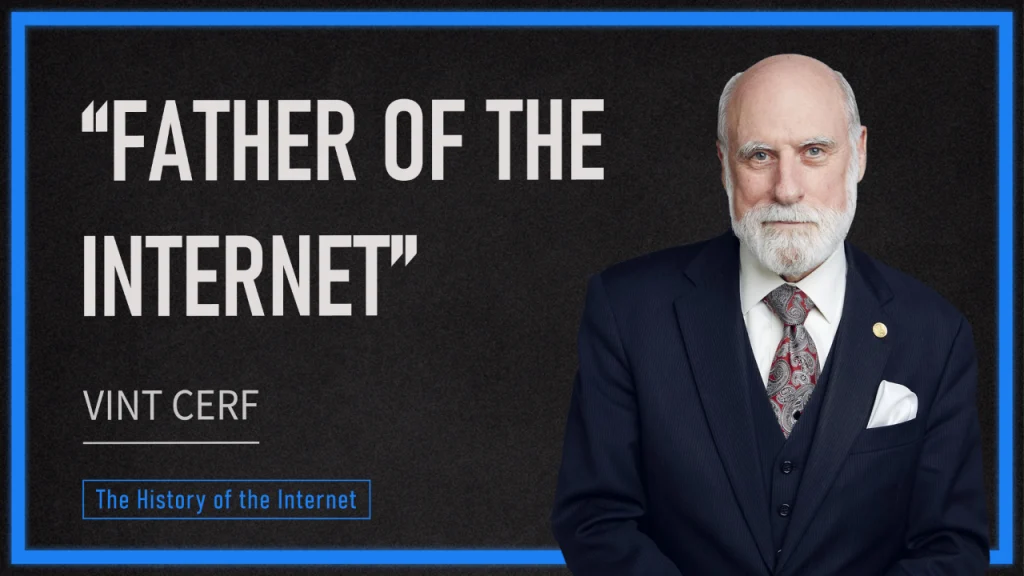

This interview is part of BTW Media’s new series, ‘The History of the Internet,’ which interviews the key engineers and computer scientists who helped build and create the Internet.

Vint Cerf, widely regarded as one of the “fathers of the internet,” has offered a fascinating look back at the chaotic, experimental, and sometimes surprising origins of the technology that underpins modern life. In our exclusive interview, he explains how what began as an exclusive U.S. Defense Department project, the ARPANET, was never initially intended to be a global public utility.

The first challenge was simply getting different computers to talk to each other. By 1972, the ARPANET successfully demonstrated packet-switching, a technology dismissed by the incumbent AT&T, which was dedicated to circuit switching. The computer-centric approach was necessary, Cerf explained, because computers “tend to connect to another computer, blast some data at them, and then shut up and go and talk to somebody else.” Packet switching allowed for the efficient time-sharing of bandwidth, enabling applications like remote access, file transfers, and, by 1971, electronic mail.

The true “internet” concept, or “internetworking,” was born out of a critical problem in 1973: how to connect the ARPANET with newer, mobile, and satellite-based packet networks without changing their core design. This led to the development of gateways (now routers) and the foundational Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and Internet Protocol (IP). After several iterations, the protocols were stabilized around 1978.

First use of the word ‘internet’

Regarding the terminology itself, Cerf clarifies the moment a much-needed abbreviation came into being: “In December of 1974 we published a request for comments… and the label said… ‘the specification of the internet transmission control protocol’ and so that was the first written use of the word internet in December of 1974.”

The Birth of IPv4

One of the most consequential decisions was allocating address space for the first version, IPv4. Based on an estimate of 128 countries, with two major networks per country, Cerf and his colleagues settled on a 32-bit address space. This decision yielded over four billion possible addresses, a number they believed was more than adequate.

“We allocated 32 bits for addresses on the internet… on the order of 4.3 billion terminations,” Cerf recalled. “And I thought while I was running the program, that’s got to be enough to do this experiment. That’s more than there were people in the world at the time.”

The advent of Ethernet and the widespread availability of the Unix operating system in the mid-1980s accelerated adoption, eventually leading to a surge in demand and a clash of standards. TCP/IP competed against the international X.25/X.75 and Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) models.

“It was not a slam dunk at all. There were lots of fights,” Cerf said. Ultimately, what gave TCP/IP the edge was its broad implementation and commercial support. “The commercialization I think is what gave the edge to the TCP/IP protocol suite.”

When Vint Cerf realised what he’d created

Cerf credits the Interop trade show, started in 1986, as the moment he truly understood the internet’s potential. By 1988, 50,000 people attended the show, with major companies like Cisco making enormous displays. Seeing their investment, Cerf recounts his epiphany: “I just stood there and I’m thinking, ‘Holy crap, somebody thinks they’re going to make money out of the internet.'” This spurred him to push for commercial access, which began with connecting the MCI Mail system to the government-sponsored NSFnet backbone in 1989.

The Future of the Internet

Looking ahead, Cerf remains engaged in cutting-edge projects, including the Interplanetary Internet—a new suite of protocols (the Bundle Protocol Suite, not TCP/IP) designed to handle the astronomical distances and frequent disconnections of deep-space communication.

“We expect to be part of the Artemis return to the moon missions,” he noted.

He also mentioned the Interspecies Internet, which aims to use AI to “connect non-human species to each other and potentially to use artificial intelligence to translate from one species to another.”