- AFRINIC paid up to $10 million in legal fees under an irregular contract with a convicted fraudster’s firm.

- Court-declared illegitimate representatives continued acting for AFRINIC, enabled by conflicts of interest at Mauritius’ company registry.

Forget the lawsuits and the boardroom dramas. The real scandal at AFRINIC is money. A confidential contract obtained by BTW Media reveals the organisation paid up to $10 million into a Mauritian law firm headed by a convicted fraudster. This contract paid inflated hourly rates and unlimited expenses for legal work carried out by people the Supreme Court said had no right to represent AFRINIC in the first place.

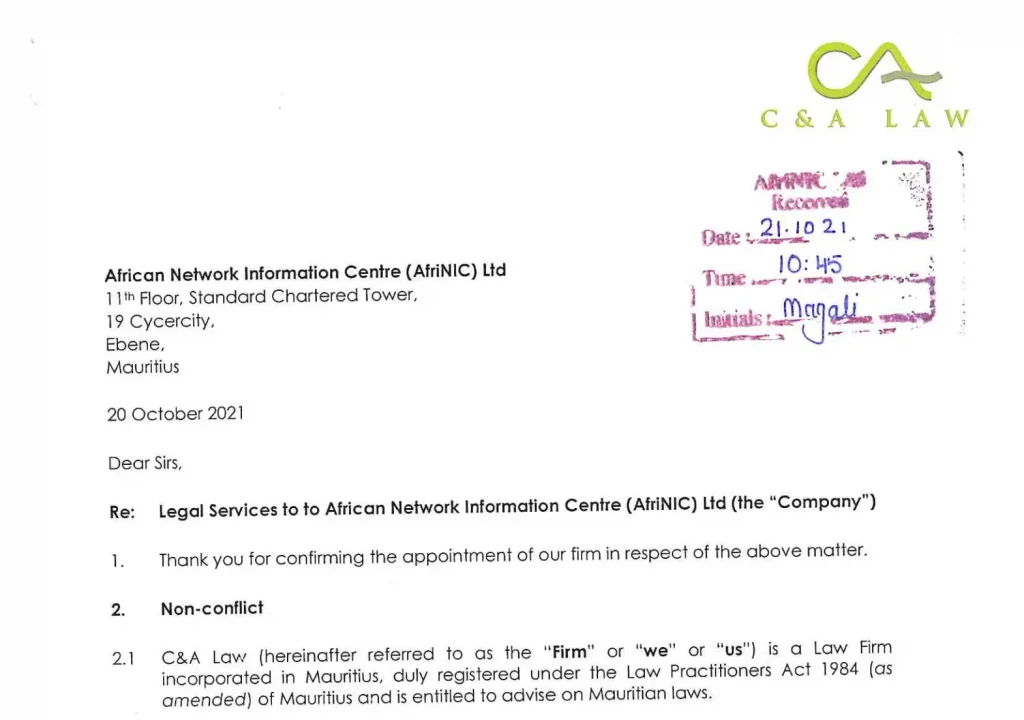

This letter, which you can see below, reveals the unsung truth – AFRINIC’s demise was almost entirely caused by its own representatives and legal operators.

For nearly two decades, AFRINIC was hailed as a proud symbol of African digital independence. Established in 2005, it became the continent’s official Regional Internet Registry (RIR), responsible for managing IP address allocations and helping Africa build its digital future. But in recent years, AFRINIC’s reputation has collapsed under the weight of corruption scandals, governance failures, and judicial interventions.

The latest revelation, uncovered by BTW Media, paints a disturbing picture of systemic financial misconduct. The leaked Letter of Engagement between AFRINIC and C&A Law reveals how the organisation spent millions of dollars on legal fees that were grossly inflated, irregularly structured, and funnelled through intermediaries with troubling personal connections.

At the heart of this story is not the external lawsuits AFRINIC was entangled in, but the internal decisions that drained its funds and entrenched a culture of mismanagement.

Also read: AFRINIC’s September elections were a flagrant violation of its own bylaws

AFRINIC’s crisis of governance

Before we can understand the scandal, we should trace AFRINIC’s decline. By 2019, allegations of corruption and the abuse of staff had put the organisation in the spotlight. Internal investigations revealed that millions of IP addresses had been secretly allocated to shell companies, implicating senior staff in fraudulent activity worth tens of millions of dollars.

Instead of resolving its internal rot, AFRINIC’s leadership embarked on years of costly and ill-fated legal strategies. Court injunctions piled up. Elections for new directors were annulled. Board members overstayed their terms and continued to represent AFRINIC even after courts declared they had no locus standi, meaning no legal authority to act on behalf of the registry.

By 2022, AFRINIC was effectively paralysed. Its board had disbanded, its CEO’s contract had expired, and Mauritius’ Supreme Court had to appoint an Official Receiver to keep the institution afloat.

It was during this period of chaos that AFRINIC’s legal expenditures ballooned, revealing how much of its crisis was not just mismanagement, but deliberate enrichment at the organisation’s expense.

Also read: Judge Bellepeau resigns from AFRINIC investigation after injunction

The $10 million legal bill

The turning point came with the disclosure of AFRINIC’s Letter of Engagement with a Mauritian firm called C&A Law, signed in October 2021. It looked, at first glance, like a standard agreement for legal representation in a dozen ongoing cases. In reality, it opened the door to financial irregularities on a shocking scale.

The contract reveals that AFRINIC agreed to pay US$1,000 per hour for “professional fees” associated with the firm’s services. That figure alone should raise eyebrows: it is a rate typically charged by top-tier King’s Counsel in London or New York, not by small firms in Mauritius. Many barristers in the UK (arguably a much more expensive market) charge less.

But the issue wasn’t just the rate. The contract’s flat-fee structure, a single hourly rate for all work performed, was highly unusual. Most law firms charge tiered rates depending on seniority: partners may bill high, but junior associates, paralegals, or clerks bill significantly lower. By setting a blanket $1,000 per hour rate, AFRINIC effectively signed a blank cheque, guaranteeing inflated invoices regardless of who actually performed the work.

Over several years, AFRINIC’s legal bills under this agreement are believed to have reached US$10 million; an extraordinary sum for a non-profit organisation meant to serve Africa’s internet community.

Also read: Smart Africa leaks thousands of AFRINIC member email addresses

A convicted fraudster at the helm

The controversy deepens when considering who AFRINIC hired.

C&A Law is headed by Goinsamy Chinien, a former barrister convicted in 1987 for conspiracy to export foreign currency. Though his prison sentence was later quashed, his conviction was upheld, and his name was permanently struck from the roll of barristers in Mauritius. Effectively, he was banned from practising law.

Despite this history, Chinien managed AFRINIC’s legal affairs for years. His firm’s letter of engagement openly states that it would “work together with Anwar Moollan, Senior Counsel, of the Chambers of Sir Hamid Moollan QC.” This raises immediate red flags: if the substantive legal work was to be carried out by Moollan’s chambers, why did AFRINIC go through Chinien’s firm at all?

In standard practice, a client hires a law firm directly; intermediaries who add no legal expertise are unnecessary. In this case, AFRINIC paid an extra layer of costs, at premium rates, for what amounted to middleman services.

Also read: Did ICANN’s lawyer illegally visit AFRINIC when the Official Receiver was away?

The unlimited expenses clause

Perhaps the most alarming part of the contract was its treatment of disbursements, the incidental expenses billed to AFRINIC on top of hourly fees. The letter allows C&A Law to charge AFRINIC for out-of-pocket costs including “phone calls, travel, parking, photocopying, couriers, binders, transcripts, research charges” and more.

Nowhere in the contract is there a cap, limit, or estimate for these expenses. In theory, AFRINIC could be billed thousands of dollars for basic office functions like printing or postage. Over years of litigation, such unchecked costs could easily have added up to six- or even seven-figure sums.

For a non-profit funded by membership fees from African internet operators, this was an extraordinary lapse in financial oversight.

Also read: ICANN CEO’s attempt to thwart freedom of the press, information

Conflicts of interest in Mauritius

The AFRINIC-C&A Law connection becomes even murkier when examining family ties.

The Registrar of Companies in Mauritius, responsible for maintaining the official company registry, is Prabha Divanandum Chinien, the wife of C&A Law’s managing partner, Goinsamy Chinien.

This dual role creates a glaring conflict of interest. Court rulings had already declared that several individuals acting as AFRINIC directors, including former chair Benjamin Eshun, had no legal authority to represent the organisation. Yet those same individuals continued to appear in court filings and, crucially, remained listed as directors in the Mauritian company registry.

The registry’s failure to update AFRINIC’s official records prolonged the chaos and gave illegitimate actors the appearance of authority. Observers argue that this cannot be separated from the fact that the Registrar herself was married to the man directly profiting from AFRINIC’s bloated legal expenses.

The locus standi problem

One of the recurring themes of AFRINIC’s downfall has been the presence of individuals who had no legal standing yet continued to represent the organisation.

In a 2023 judgment, the Mauritian Supreme Court explicitly ruled that neither Anwar Moollan nor Benjamin Eshun had locus standi to appear in court on AFRINIC’s behalf. Eshun’s directorship had expired; Moollan, engaged through Chinien’s firm, was not recognised as having authority.

Despite this, both continued to file appeals and motions in AFRINIC’s name. These actions prolonged litigation, drove up legal costs, and delayed any resolution to AFRINIC’s governance crisis. Each new application or objection generated more billable hours for C&A Law under its exorbitant $1,000-per-hour contract.

Mismanagement or corruption?

Supporters of AFRINIC’s former leadership argue that the chaos was the product of incompetence and weak governance, not outright corruption. But the evidence in the engagement letter suggests otherwise.

The inflated fees, the unnecessary intermediary, the unlimited expenses, the use of representatives without authority, and the conflict of interest at the heart of Mauritius’ company registry, all point to more than negligence.

They reveal an organisation whose leadership was willing to waste millions of dollars of community funds. At worst, they suggest deliberate enrichment schemes orchestrated by individuals in positions of trust.

AFRINIC’s future

Today, AFRINIC has elected a board, after the September elections went ahead (despite yet more evidence that the elections were not held according to AFRINIC’s own bylaws, or in accordance with the Mauritian Companies Law). They will be tasked with restoring stability and putting operations back on the front foot. Even these processes have been plagued by suspensions, annulments, and disputes over voting procedures.

Meanwhile, Several other African nations, including South Africa, Rwanda, and Nigeria, have reportedly expressed interest in becoming AFRINIC’s new home. They question whether AFRINIC remain headquartered in Mauritius at all. With a convicted fraudster’s firm profiting from its legal affairs, and with his spouse overseeing the company registry that legitimises illegitimate directors, Mauritius’ credibility as a host nation is under fire.

A letter that changed the narrative

The leaked engagement letter may prove to be the most important document in AFRINIC’s troubled history. It strips away the rhetoric of technical disputes, community politics, and corporate rivalries, revealing the simple truth: AFRINIC’s greatest threat was its own leadership’s willingness to bleed the organisation dry.

The $10 million question remains: how much of that money was spent on genuine legal representation, and how much was siphoned away through inflated fees, unlimited disbursements, and compromised governance structures?

Until AFRINIC answers that, its legitimacy as Africa’s internet steward will remain in doubt.