- Critics warn that CAIGA risks entrenching political control rather than fixing AFRINIC’s deep-rooted governance failures, raising urgent questions about legitimacy and autonomy.

- Smart Africa’s state-driven model, backed by ICANN funding and participation, has triggered concern that Africa may lose—not gain—control over its internet future.

Is CAIGA truly a reform—or a political override?

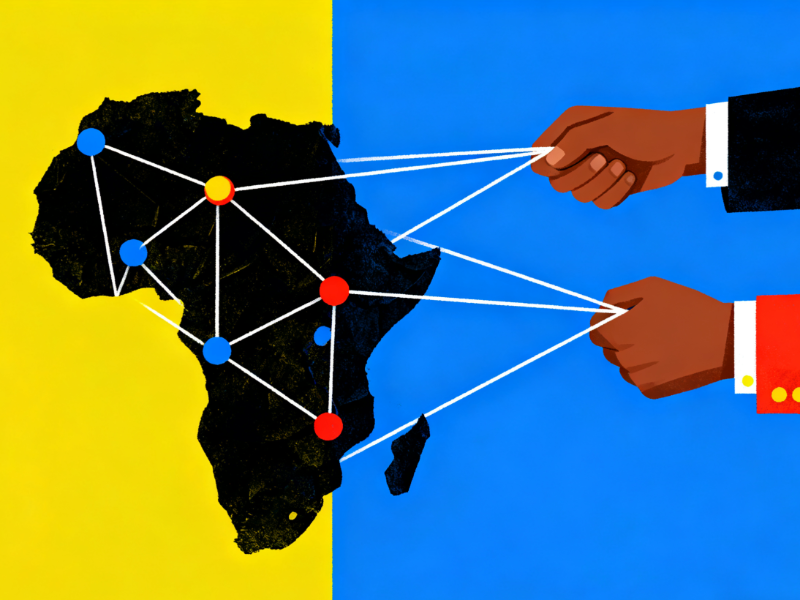

The Continental Africa Internet Governance Architecture (CAIGA) is being promoted as the next phase of Africa’s digital governance. Smart Africa argues the framework will harmonise rules and stabilise institutions after AFRINIC’s years of turmoil. But the proposal’s structure raises a fundamental question: is CAIGA a governance reform, or a political mechanism designed to override community authority?

AFRINIC’s failures are real—mismanagement, repeated election collapses, lawsuits, and the erosion of public trust. Yet critics argue that replacing a broken system with a government-centric one does nothing to solve the underlying problems. Instead of strengthening accountability, CAIGA risks placing core internet decisions in the hands of political actors whose priorities may not align with technical independence or regional autonomy.

Also Read: CAIGA does not reduce internet fragmentation in Africa, it centralises power

Why did ICANN support a model it claims to oppose?

Many African stakeholders are asking why ICANN—an organisation that built its global identity on defending bottom-up, multistakeholder governance—provided funding, institutional support, and working-group participation for Smart Africa’s CAIGA blueprint. ICANN’s leadership insists the funding was neutral and unrelated to AFRINIC governance. But the blueprint itself clearly outlines governance structures that would allow governments to influence or override AFRINIC’s community processes.

This contradiction has led experts to question whether ICANN is applying different standards to Africa than to Europe, Asia or the Americas. If CAIGA’s model would be unacceptable for RIPE NCC, ARIN or APNIC, why is it being encouraged—or even enabled—in Africa?

Also Read: Why CAIGA cannot improve Africa’s internet security

Who benefits—and who loses—under CAIGA?

Before CAIGA moves any further, Africa must confront several high-stakes questions about its real impact. At the centre of the debate is whether CAIGA will preserve community-led governance or quietly replace it with government-driven authority that prioritises political interests over technical independence. Critics worry that the framework could introduce new forms of fragmentation, creating tension between states and the existing internet community while centralising oversight in ways that undermine regional autonomy.

There are also concerns about whether CAIGA will genuinely enhance African digital sovereignty or simply trade it for a new layer of continental bureaucracy that weakens transparency and accountability. Ultimately, the key issue is who will hold final authority over Africa’s internet resources—its community of operators, engineers, and users, or a political structure enabled by Smart Africa and legitimised by ICANN’s support. Until these questions are addressed openly and honestly, CAIGA risks becoming a mechanism for political consolidation rather than meaningful reform of African internet governance.